|

Posted at 12:10 am on December 10, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

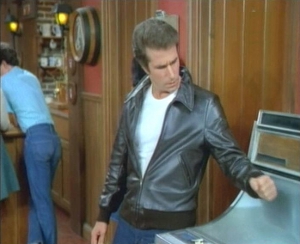

The Fonz could knock down doors with a slap of his hand, summon any girl with a snap, and most often on the show displayed his classic power of fixing the jukebox by banging on it. It’s a seductive fantasy that one might be able to fix a complex piece of machinery through an application of blunt force, without having to worry about the intricate mechanisms that actually allow the machine to work. Unfortunately, this is the mentality that has reigned for decades in applied public policy. Is the economy broken? Bang on it. That’ll get it chugging along again. Wait, that didn’t work? You didn’t bang it hard enough. Or maybe your leather jacket needs to be a little cooler next time. At any rate, it’s your fault. If you’d only smacked the economy the way that Fonzie showed you, it totally would have worked. Economic prescriptions thereby stem from a non-falsifiable tenet of faith in a grown-up power fantasy. This kind of magical thinking convinces many because it is accompanied by a veneer of rigorous thought. There are even equations! Surely, equations are scientific! But as economist Don Boudreaux pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

Keynesian macroeconomic variables lump heterogeneous goods and services into undifferentiated masses, no longer to be understood as the complex workings of a dynamic system of social cooperation. But just because you can gather a bunch of statistics and aggregate them into a variable doesn’t mean that the variable has a meaningful application to the real economy. If you want to fix a jukebox in real life, a mechanic might be able to get the job done by tinkering with the machinery until each piece once again functions correctly. It’s easy for people who have a facility with physical forms of engineering to take a similar view of the economy, thinking that if only the right people were in charge, they could tweak policy here and there to ensure successful outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith explained why the economy can’t be successfully engineered in such a way:

Even though an economy can’t be planned, or even tailored, successfully from on high, that form of scientism is at least understandable. It at least takes into account a small measure of the complexity of decentralized economic activity, even if it doesn’t — indeed, can’t — consider the rest. Keynesian macroeconomics is far worse, shunning even the scientistic attempt to grapple with at least some heterogeneous microeconomic factors as being the causal source of economywide trends. Instead, they insist that policymakers expropriate as much cash as humanly possible and wallop the economy with it as hard as they can. Economist Steven Horwitz summed up the real prescription for economic recovery:

In the end, the economy is not a jukebox, and neither a mechanic nor Ben Bernanke in the coolest leather jacket ever made can save it from its turmoils. Instead, the economy is made up of hundreds of millions of people with billions of plans, many of which fail but some of which succeed. Nobody knows for sure which plans will pan out in advance — not the people making them, and certainly not their public officials. Only by letting individuals, alone or in voluntary association with others, respond to local conditions with unique knowledge can the best plans be discovered, expanded, and replicated. That process is made much more difficult when they face continual interference from central planners who only pretend they can know what’s best. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 12:05 am on October 19, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

Here’s a great cartoon from Completely Serious Comics published earlier this year, currently being passed around on Facebook by critics of Keynesian stimulus: I doubt the cartoon’s creators were thinking about government stimulus of aggregate demand when they conceived this, so it has become a piece of appropriated satire. And, like pretty much all great satire, it doesn’t play completely fair with its target. Even so, it contains a substantial nugget of truth. Readers of this blog who are familiar with the book from which it takes its name will be well-acquainted with the broken window fallacy, first created as a parable by Frédéric Bastiat and later appropriated by Henry Hazlitt, who applied it to a mid–20th century economy. In a nutshell, the parable explains why destruction doesn’t make a society wealthier. It may stimulate short-run economic activity as people rush to replace and rebuild what they’ve lost, but always at the expense of overall prosperity. Within the past few years, Bastiat’s and Hazlitt’s critical heirs have applied the fallacy again and again to modern Keynesians. Here’s a video that does exactly that to Paul Krugman’s application of Keynesian theory to the destruction wrought by terrorist attacks (featured on this blog last year): One objection to this line of thought could be that the broken window parable doesn’t apply to general stimulus, because government spending absent a disaster isn’t the same thing as destruction, and so isn’t analogous with a broken window. One response to this objection would be that the broken window parable is part of a larger essay about the unseen effects of various types of economic action. People explaining the arguments in the larger essay, which does indeed include government spending, might reasonably refer to them by invoking the best-known portion of that essay, the parable of the broken window. Conjuring the whole of an essay by referring to one part would be a kind of allegorical synecdoche, if you will. Another response would be that spending may not destroy useful physical objects, true enough, but it does divert resources from more productive to less productive uses. Although private-sector businesses can’t be sure what their most productive potential investment will be, the government is by nature even less informed and therefore less capable of investing wisely. Siphoning resources from the private sector to the public sector destroys wealth, even if it doesn’t destroy specific goods. An allegory of a destroyed object certainly applies to the reality of destroyed wealth. Keynesian apologists, and even some non-Keynesians, have cried foul in still more nuanced ways, pointing out that advocates of government stimulus don’t per se want destruction, and may not even think it will bring increased wealth, but think instead that it will increase short-term economic activity, increasing employment and smoothing over economically troubled times. There are indeed shades of meaning and intent here. Believing that destruction may benefit the economy in some structural way, thereby sustaining short-term damage for long-term gain, isn’t the same thing as thinking that any individual act of destruction will increase economic wealth. After all, as Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, entrepreneurs engage in short-term “creative” destruction all the time, writing off temporary losses as a necessary cost of pursuing their visions for long-term productive investment. The evidence, however, shows that government spending intended to stimulate the economy and smooth out the business cycle instead exacerbates the business cycle, leading both to higher peaks and lower valleys. As Russ Roberts pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

When there’s a downturn in the business cycle, there’s a structural problem with the economy — too many people in some occupations, not enough people in others. General stimulus provides no economic information about where people should go to find sustainable productive work, meeting real demands by providing the goods and services that people want rather than the trumped-up illusory demand prompted by government spending. You can’t build a healthy body on a string of sugar rushes, and you can’t build a healthy economy on a series of artificial top-down influxes of cash. Stimulus only spurs some sectors of the economy by dampening others, whether present or future. The more that government officials tamper with the economic signals that let entrepreneurs know when they should invest and when they should steer clear, the more skittish investors become. Regime uncertainty entrenches malinvestment, and keeps the economy limping along. So, Keynesians, please stop celebrating destruction as a cure for economic ills. If truly creative destruction needs to happen in order to move less productive resources into more productive uses, private-sector entrepreneurs have the decentralized knowledge necessary to determine which of their own resources need to be replaced or reshuffled. Government officials do not. The only real cure for our lagging economy is for the government to quit breaking windows. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 1:44 am on February 5, 2011, by John W. Payne

I used to follow foreign policy with a passion that bordered on obsession. I’ve always been a news junkie, but, like many Americans, my focus shifted to foreign affairs after 9/11. But after about five or six years, I started drifting away from it somewhat, I think mainly because it just got too damn depressing. However, the wave of protests that has erupted in the Arab world over the past two months has not only rekindled my interest in the region but also given me some hope that its political problems are not completely intractable. Perhaps the most heartening aspect of all this is that it seems to be a legitimate groundswell of popular opposition to all the repressive regimes from Yemen to Algeria. The most obvious historical parallel is to the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks during World War I in 1916, but that was primarily composed of Bedouins from the Arab peninsula–not a truly pan-Arab phenomenon. To find a similar string of uprisings across many nations, you would have to go back to the Revolutions of 1848 that swept almost all of Europe and spread the idea of national self-determination far and wide. Like the protests we see today, those revolutions were all driven by local problems and concerns, but participants frequently drew inspiration and solidarity from the knowledge that similar events were unfolding in neighboring countries. Of course, bottom-up political change does not square with accepted faith of partisan hacks–both Democratic and Republican–that Washington is the prime mover in all earthly (and, in all likelihood, cosmic) affairs. It has been amusing to watch people absurdly attribute the millions of people gathered in Tahrir Square to Obama’s speech at Cairo University in 2009. Even more outlandish is the view endorsed by a few neoconservatives that recent events have somehow vindicated George Bush’s foreign policy of implementing democracy at the end of a bayonet. Left unsaid is that part of Bush’s (and Obama’s) foreign policy was propping up dictators like Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak with billions of dollars in foreign aid. Moreover, I hate to break it to them, but the rest of the world does not revolve around the United States (and the United States does not revolve around Washington D.C.), and you can’t centrally plan and export a revolution. The protesters have a variety of reasons for their actions, but a speech by an American president and an eight-year-old war hundreds of miles away are probably way down the list. These revolutions are spontaneous orders–like markets or civil society–which governments do not respond to well, both because they frequently demonstrate how unnecessary the government is and they lack formal hierarchies. Most people believe that without government, society immediately turns into pandemonium, but despite the fact that the Egyptian government has been effectively shut down, the Egyptian people themselves are coming together to provide the services they need. In this video, Egyptians volunteer to clean up the streets, deliver medical care, and distribute free food to demonstrators. The New York Times also ran a superb article on Monday describing how regular Egyptians are keeping their society functioning even in the midst of great turmoil:

And being leaderless is is actually one of the revolution’s great strengths. If there was a leader or small group of leaders, Mubarak could attempt to co-opt them with money or positions of power. In fact, this is precisely what he is attempting to do with the army by appointing General Omar Suleiman to the vice presidency. A government can deal with another hierarchical institution, but an amorphous blob consisting of millions of pissed off people is utterly confounding. There is only one thing Mubarak or any other government can do to retain power in such a situation, and it is best explained by an Egyptian quoted in that Times article:

Mubarak’s government has been exposed as malevolent and unnecessary, so he has little choice but to create the problem he purports to solve. Many Egyptians are reporting that when caught, looters frequently turn out to be plainclothes police officers loyal to Mubarak. When it comes down to it, there is really only one tool in government’s toolbox: a big fucking club, and Mubarak is using it to spread fear and instigate violence, which he hopes will make people submit to his rule once more. The revolts in Egypt and elsewhere could still go terribly, terribly wrong. Mubarak could weather the storm and rule the country until his death. Or a radical Muslim faction could take power and institute a theocracy. Or a new government could start another war with Israel. Although I’m guardedly hopeful, I know that these things usually end in tears. That said, what these protests have already shown Egypt, the Middle East, and the whole world is that people do not need a strongman; they do not need a government. Society is an organic process, and it gets along pretty well without leaders. The lesson is there, but whether enough people will listen remains to be seen. Headline reference here. Filed under: Foreign Policy, Spontaneous Order Comments: Comments Off on Tough Luck for (Un)elected Officials, The Beast Ya See Got Fifty Eyes

|

When I was a kid, I loved watching

When I was a kid, I loved watching

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."