|

Posted at 11:31 am on October 8, 2013, by Wirkman Virkkala

This weekend, Justin Stoddard brought up Arthur Koestler’s views on faith, in the context of Mises on human action. The discussion at first struck me as tangential to the main thrust of the first chapter of Human Action, which we both read as part of an attempt at a tandem, co-ordinated reading. But considering that in that first chapter Mises tries to mark the differences between praxeology, the theory of action, and other domains of thought, such as psychology, epistemology, metaphysics, etc., and that faith would normally be thought to reside somewhere in these other domains, perhaps it is not so tangential. Perhaps it is a good prefatory discussion. Like Justin, I see that the common maxim that warns us that you “cannot reason a person out of a position that person did not reason himself into” is obviously false. It may be that I did not “reason myself into” the religion of my family; it was “in the air,” a part of my heritage as much as the house I lived in the and the forest nearby: I did reason myself out of it, though. Most people never accomplish any task of a similar nature. They fall into a religion, or an ideology, like they fall into love: the object of adoration was near at hand, and quite serviceable, and seemed willing to reciprocate and meet some basic needs of the psyche. Most people become liberals or conservatives in this way, and I’m sure some libertarians are born this way, too. It was Justin, also, who brought up matters of belief as an element of reason, rationality. This is not the primary object of Mises’ interest, in Human Action. But, to clear the way for future commentary, I’ll consider, briefly, the doctrine of the minimum wage legislation, which Justin mentioned as if a stand-in for the many positions of libertarianism (a social philosophy Justin and I both hold to). And I’ll do this in frank autobiography. When I was a teen, and extricating myself from the faith of my mother and my aunts, et aliae, I was also beginning the process of settling on a political ideology. I considered myself a liberal. I deemed my basic attitudes liberal, and on some important issues I favored liberty over regulation. But I had been taught in school and from the TV (and in part from my encyclopedia set) that concern for the poor had led to laws like those establishing a minimum wage, and I was basically accepting of the practice, and many others of our society and its government. But I had the wit enough to see that minimum wage laws were comparable to laws about marriage and sex (say, the prohibition of prostitution) that I objected to. So I thought the only rational thing to do was consider the case against the minimum wage, as made by some economists and most libertarians. That case involved scarcity, wealth production, supplies and demands, etcetera, and I became convinced that minimum wage laws didn’t have the univocally good results hoped for and trusted in — as, I could see, a matter of faith — by proponents of the dirigiste state. I knew some folks who, without blinking, supported minimum wage laws and legal prostitution, both, without blinking an eye. And yet it was obvious that laws against prostitution were of a similar nature to minimum wage laws. Both prohibited certain contracts at certain rates. Both had seemingly plausible arguments in their favor, but neither worked as their proponents thought. The “faith” element, here, is the belief in the advisability of a program while refusing to believe in the negative effects of the program in question, or of judging the program on the general results, or with reference to those results. Some evidence must not be not considered. And the world is a complicated enough place that one can easily shield one’s eyes from things one doesn’t want to see. There’s always something else to look at. In the case of the political opponent of prostitution, it’s the inherent vileness of the activity as it is when the practice is illegal, and the pure morality of sexual activity confined to pure barter in bilateral monopoly. The negative effects of anti-prostitution laws are just a “cost of promoting the good.” Or, it is asserted, though without much careful thought, “the cost of ameliorating a great evil.” Mutatis mutandis, it is just so with the opponents of low wage contracts. The suffering of the people who must endure low-paid work gets concentrated on, as does, even more so, the imagined alternative: higher wages — hooray! The idea that the actual alternative under minimum wage laws is that at least some segment of the low-skill labor force will suffer no employment? Blankout. Not addressed. I noticed this at the time. I was the only liberal I knew who had looked squarely at the arguments made against minimum wage laws. And when I would relate these arguments back to fellow liberals, they dismissed them, not merely with lack of interest, but derision. These people who made them did not care about the poor! And I have heard this reaction many times since. My own take was that a person who wishes to help the poor, upon hearing that one’s chosen means to do the work would not work, instead of rejecting the news, would be concerned, and look into it. Why? Because of the ostensible aim, helping the poor. If one did not look closely at the challenge, then it was obvious that helping the poor was not the real aim. The real aim might be something more like “seeming to help the poor” or “appearing moral.” And this is where my commonality with Mises becomes clear. He aims to provide reason to the processes of causation from human choice, to clear up the confusions, and to find the regularities in social causation. His science, that of a rather formal ends and means structure, he calls praxeology. It is the underlying principle to much of the work done by economists up to his time. As Mises saw it, the main opponents of the development of such a science have been those whose approach to social life and public policy relied too heavily on faith and defensive inattention. And so Human Action, in the course of developing the principles of praxeology, also elaborates quite a few critiques of the dominant faiths of the age — many of which remain dominant after all the years since Mises first published his great book. Praxeology does not itself require faith. It requires careful reasoning to figure out. One reasons one’s way into an understanding of economics. But it is possible to sloppily approach a doctrine of laissez-faire, and proceed on faith. I know many libertarians who rely entirely on their bets about the world, and do little actual investigation into the reality of the underlying claims. That’s only natural. Human beings have limited time. Not everyone can be an economist, or philosopher. But I don’t think we should equate those libertarians whose approach is almost entirely intuitive with those who have engaged in deep study. The libertarian faith and the libertarian wisdom have at least some differences. Much of it relies on what we bring to the issues. A deep prejudice for freedom is a great thing in a person, and it often leads to the full flower of a libertarian individual. But it’s not enough. Not if you really want to understand the world. I am not sure that I’ve addressed what Justin was broaching. I’m pretty sure I have not in any way summarized the first chapter of Human Action. But perhaps now we can proceed to a discussion of the book? We can return to the issue of faith — and, in general, of non-rational approaches to belief and action — as we proceed. Filed under: Economic Theory, Philosophy Comments: Comments Off on Reasoned Out, Reasoned In

|

|

Posted at 8:54 pm on September 23, 2013, by Wirkman Virkkala

In an economic downturn, when massive business failures appear simultaneously, owners of the means of production need to find new uses for their discarded capital-intensive production processes, and investors need to find new forward-looking enterprises to place their funds, in hopes of some future return. This is part of the recalculation necessary during the cluster of business errors called a depression. The terminology I’m using is that of the Austrian school, of its capital theory as well as its theory of the business cycle. And I’m applying it to this very blog. Which has been comatose for some time. I invite the former participants in The Lesson Applied to give Ludwig von Mises’ Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, a careful reading. Or re-reading, as your case may be. Writers, contact me on Facebook and I’ll sign you up for Reading Matters, a Facebook group that will handle some of the technical matters of our co-ordinated reading. I propose to read this long treatise chapter by chapter, moving on when a consensus of active readers agree. This blog will be location for our ruminations. That is, we will discuss the book and its ideas here. Perhaps after we’ve read Human Action, the blog will revive back to its original purpose, of exploring the ramifications of policy upon market society, beyond stage one, as Thomas Sowell so neatly put it, in a Hazlittian spirit. Always, lingering in our thoughts, will be Bastiat’s insight: where in Mises’ work does it fit? Filed under: Economic Theory, Education, Philosophy Comments: Comments Off on Repurposing Capital: Human Action

|

|

Posted at 12:03 am on September 12, 2012, by Lee Sharpe

Recently, Krugman wrote that if you think the iPhone 5 will boost the econonmy, then you believe in the Broken Window theory. The Broken Window Theory, more accurately described as the Broken Window Fallacy, is the belief that destruction can boost the economy, as people, companies, and governments spend to replace them. Krugman is a big proponent of this plan, even going as far to argue that spending to prepare against a space alien threat would be good for the econonmy, even if it turned out to be false. But I’ll focus here on Krugman’s iPhone argument. He writes:

If the iPhone 5 boosts the economy, and I believe it probably will, it’s because consumers feel it will create more value for them than the other uses they may have for their money. The “destruction” Krugman refers to people’s previous phones. But their other phones are not destroyed! They could sell their old phone, give it to a family or friend, donate it to charity, or any number of other options. But they find purchasing a new phone to be worth it. If their previous phone was so truly bad that it doesn’t have other uses anymore and the best thing to do is throw it away, then by definition nothing of value has been lost, so even in this case there is no real destruction as meant by the Broken Window Fallacy, where the owner of property suffers an involuntarily loss. But suppose there was an involuntary loss. Let’s say their old phone broke down and was out of warranty. In this case there certainly was destruction, and the person is buying the new phone to replace their old one. Maybe this is the case that Krugman means, although I would argue this is small minority of the iPhone 5 purchasers. But if these people wouldn’t have bought an iPhone 5 if their broken phone still worked, is that really a boost to the economy in the aggregate? Only if you look at what is seen (buying the iPhone 5 and creating employment in that industry). But we also need to look at what is unseen: Not buying the iPhone 5 would mean spending that money on something else, which creates employment in whatever industry the money would be spent on otherwise. So really when the person’s old phone breaks, the economy is down one phone, which makes it worse off, not better. Krugman attacks the Broken Window fallacy, as he doesn’t believe it’s a fallacy at all. But the truth is that economic growth created by the iPhone 5 will be because it creates more value for consumers than it costs them to buy it, not because of any destruction that is happening. For a more thorough explanation of why the Broken Window Fallacy is a fallacy, I highly suggest watching this video: Filed under: Economic Theory Comments: 3 Comments

|

|

Posted at 12:26 pm on August 14, 2012, by Brian McCall

A question to you of a chicken and egg sort. If you have a group of people in a flat empty world with nothing in their possession, how do you get them to have things? Would you: A) Give everyone pieces of paper with faces on them, call it money, and tell them to wait for someone to devise a way to accumulate those pieces of paper for himself, and hope that the means he devises results in people getting stuff? B) Or would you give them tools, machines, and other various means to produce things they want? Would you give the knowledge and the means to make the tools? The answer here should be obvious. Yet, I am always astounded to hear people say that the way to generate economic growth is to stimulate demand, or speak as if the money itself has some kind of intrinsic value. Demand is an artifact; it is a consequence of production, not its progenitor. It wasn’t the vast network of highways that induced Henry Ford to start building cars. It wasn’t the airport runway that induced the Wright Brothers to put wings on a lawnmower. And it isn’t the existence of currency that induces people to make things. We make things because we want things. Money is merely the means by which we coordinate and communicate our individual desires and interests to others. If no one else is making anything, currency doesn’t communicate anything. A currency is not a measure of the total demand. It is a measure of overall production. The dollar is the inch on this yardstick. I explained it this way the other day: If you have a length of rope, and you wish it were longer, you don’t make a longer rope by making more notches in your yardstick, and call the new divisions “inches”. You still have the same length of rope, just smaller units of measure. Your inches are shorter, and it is a deception to say that just because now it takes more “inches” to measure the same length of rope, that you have a longer rope. So consider this when someone claims that the economy isn’t growing because no one has money, or that companies are hording it all. Well, that makes just about as much sense as saying you have a shorter rope because you’ve erased some notches and now your “inches” are longer. Of course, there is a general kind of demand that the production takes advantage of, but this is a generic phenomenon that doesn’t change or modulate in intensity. A demand for the needs and comforts of life are not specific, and are always present. But the means by which they are satisfied are specific and can take an infinite variety of forms. So it is not merely enough that humans will always want and demand ways to conserve their energy and save labor. That is a given. Nor can that kind of demand be stimulated by giving out pieces of paper. Nor will handing out pieces of paper get you from point A, that generic, formless and inchoate sort of demand to something as specific as an internal combustion engine — the internal combustion engine being only one way that general demand can be satisfied. To perhaps borrow from Keynes’ interpretation of Say’s Law, the production of internal combustion engines creates a demand for internal combustion engines. Filed under: Economic Theory Comments: Comments Off on Demand Is a Consequence of Production

|

|

Posted at 12:10 am on December 10, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

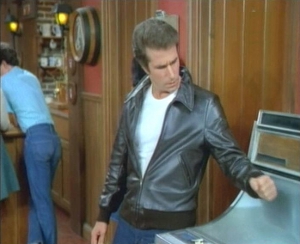

The Fonz could knock down doors with a slap of his hand, summon any girl with a snap, and most often on the show displayed his classic power of fixing the jukebox by banging on it. It’s a seductive fantasy that one might be able to fix a complex piece of machinery through an application of blunt force, without having to worry about the intricate mechanisms that actually allow the machine to work. Unfortunately, this is the mentality that has reigned for decades in applied public policy. Is the economy broken? Bang on it. That’ll get it chugging along again. Wait, that didn’t work? You didn’t bang it hard enough. Or maybe your leather jacket needs to be a little cooler next time. At any rate, it’s your fault. If you’d only smacked the economy the way that Fonzie showed you, it totally would have worked. Economic prescriptions thereby stem from a non-falsifiable tenet of faith in a grown-up power fantasy. This kind of magical thinking convinces many because it is accompanied by a veneer of rigorous thought. There are even equations! Surely, equations are scientific! But as economist Don Boudreaux pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

Keynesian macroeconomic variables lump heterogeneous goods and services into undifferentiated masses, no longer to be understood as the complex workings of a dynamic system of social cooperation. But just because you can gather a bunch of statistics and aggregate them into a variable doesn’t mean that the variable has a meaningful application to the real economy. If you want to fix a jukebox in real life, a mechanic might be able to get the job done by tinkering with the machinery until each piece once again functions correctly. It’s easy for people who have a facility with physical forms of engineering to take a similar view of the economy, thinking that if only the right people were in charge, they could tweak policy here and there to ensure successful outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith explained why the economy can’t be successfully engineered in such a way:

Even though an economy can’t be planned, or even tailored, successfully from on high, that form of scientism is at least understandable. It at least takes into account a small measure of the complexity of decentralized economic activity, even if it doesn’t — indeed, can’t — consider the rest. Keynesian macroeconomics is far worse, shunning even the scientistic attempt to grapple with at least some heterogeneous microeconomic factors as being the causal source of economywide trends. Instead, they insist that policymakers expropriate as much cash as humanly possible and wallop the economy with it as hard as they can. Economist Steven Horwitz summed up the real prescription for economic recovery:

In the end, the economy is not a jukebox, and neither a mechanic nor Ben Bernanke in the coolest leather jacket ever made can save it from its turmoils. Instead, the economy is made up of hundreds of millions of people with billions of plans, many of which fail but some of which succeed. Nobody knows for sure which plans will pan out in advance — not the people making them, and certainly not their public officials. Only by letting individuals, alone or in voluntary association with others, respond to local conditions with unique knowledge can the best plans be discovered, expanded, and replicated. That process is made much more difficult when they face continual interference from central planners who only pretend they can know what’s best. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 9:42 pm on December 1, 2011, by Wirkman Virkkala

The good folks at Coca-Cola really want to innovate. They probably admire the late Steve Jobs. They’ve lots of neat ideas. Helping polar bears is one of them. So, to honor the polar bears (or at least ballyhoo their cause and plight), Coke folk changed the color of the can of their main product, Coca-Cola™. They made it white. You know, “polar” color. And then came the uproar. Coke buyers didn’t like it. Many returned the product, thinking that it was either Diet Coke (whose silver can is, actually, very similar to the new white can) or else a modified product. A few Coke drinkers said that the drink tasted different. There was general confusion, as reported in the Wall Street Journal:

Obviously, this is another innovation from Coca-Cola that didn’t take – reminiscent of the infamous “New Coke” of a few decades ago. Coca-Cola’s clientele was so negative that the august Atlanta company switched plans, and is now switching back to the red cans we all know and love, far ahead of schedule. A lesson for us all. Consumers are sovereign. You can innovate up and down your line, but if consumers aren’t buying, you aren’t selling. The doctrine of consumer sovereignty was defended, in the 20th century, by two curmudgeonly economists, W.H. Hutt and Ludwig von Mises. The word choice was spot-on. “Consumers are sovereign” doesn’t mean that producers are meaningless. But the sovereign(s) have the last word, it’s the sovereign who must be pleased. And that’s what capitalism is all about. This lesson is probably hard on the innovators at Coca-Cola. Take the lame ending of that Wall Street Journal article:

Yes. But not distinct enough. And besides, the customer is always right. Well, right in the one way that matters most on the market, right in being sovereign. Note: I’m quite aware that the concept of consumer sovereignty is a metaphor, really, and not a technically pristine term. It was introduced by Hutt and Mises to counteract the nonsense now once again popular, the idea that corporations “push” us to do things against our will. This is patent nonsense, at least when it applies to the trades we make, the things we buy. We are pulled by producers, yes. But not pushed. We have the means to object. We can take our money elsewhere. We can simply not buy the product. As proven, once again, by the folks who drink Coke. Filed under: Economic Theory Comments: Comments Off on Coke Buyers Are Sovereign

|

|

Posted at 10:30 am on November 6, 2011, by Justin M. Stoddard

First, allow me to clarify a few points about the video below before I start into the meat of the matter. The video is obviously edited — for what purpose, I do not know. It could have been to cut down its length or to stitch together a narrative that puts the person being interviewed in the worst possible light. Though, admittedly, given his statements, I don’t know how that’s possible. I understand that people who are put on the spot with a camera in front of their face are going to stammer and search for words. After seeing thousands of these kinds of videos, I’m convinced that people generally do not do well when confronted with on-the-spot interviews.

There are some awkward questions that need to be asked in response to this assertion. Besides the obvious catchy “one percent of the people own 43 percent of the wealth” trope, why not move that arbitrary line to the top five percent? If the top one percent own 43 percent of the wealth, wouldn’t it follow that the top five percent own even more of the wealth? How about the top ten percent? The top 25 percent? The arbitrary line is chosen because it fits nicely into the idea of the proletariat struggling against the bourgeois. What is being insinuated here is the top one percent own the means of production while the 99% are the factors of production. How is the “1 percent” being defined here? One percent of the population of the United States or of the population of the world? The question matters a great deal, for a couple of reasons: One percent of the population of the United States is a little more than 3 million people (approximately the population of Mississippi). Just playing the numbers game, it strains all credulity to accept the assertion that the more than 3 million people being referenced here don’t produce anything. One percent of the world’s population is about 70 million people (approximately the population of California, New York, and Ohio combined). Of course, this takes credulity to the breaking point. The question hardly needed to be asked. The only population statistic being used here is the population of the United States. The OWS crowd skirts over the fact that if they were to count the entire population of world, the majority of them would end up in the top 1 percent of people who control wealth. That’s simply an argument they dare not broach. I’ve addressed this briefly here, but I’ll expound on it just a bit. Even adjusting for purchasing power parity, if you make $34,000 or more per year, you are in the top 1 percent of world income earners. Income disparity between someone who makes $34,000 and someone who makes $500,000 per year in the United States seems pretty significant, but not nearly as significant as the income disparity between someone who makes $34,000 per year in the United States and someone who makes $7,000 dollars per year in India, or $1,000 per year in Africa. The standard argument against this line of reasoning goes like this:

Lest I be accused of making up my own argument to refute, that’s a response I got on a recent Reddit thread addressing what I said above. At first blush, this makes quite a bit of sense. Commodities do seem to be more expensive in the United States than they are in the Sub-Sahara (unless you are living in a country with hyper-inflation). Earning $1,000 per year will certianly not give you the purchasing power to buy or rent a house or an apartment. You may or may not be able to afford transportation. Food and clothing would also be difficult to acquire. But, one is tempted to ask; would you rather live in the United States with an income of $1,000 per year or in Sub-Saharan Africa with an income of $1,000 per year? Here are the two main problems I see: First: The United States (and other First World countries) have many orders of magnitude more consumer goods and commodities to choose from than all of the Sub-Sahara put together. In the United States, $1,000 goes much further because there is so much more you can do with it. You must also consider basic welfare entitlements to every poor citizen in the United States to be used for food, shelter and clothing, along with other factors of income like child support payments and not being required to pay taxes. It further discounts the ability to barter for goods, rely on charity, and utilize the cast-offs of the rich and middle class. Our country is awash with high-class “junk.” It is very easy to acquire clothes, furniture, gadgets (TVs, microwaves, phones, radios, etc.) just by asking for it. It’s unbelievable how much stuff the well-off just leave on the curb for others to pick up. Whole virtual communities like Freecycle and Craigslist thrive around the concept of either exchanging these types of goods or just giving them away. If you are savvy enough, it is possible to get hundreds of dollars worth of name brand products for free through the practice of extreme couponing. There are literally hundreds of blogs dedicated to the concept of extreme frugality, meaning there are people in this country who choose to live well below the poverty line by recycling, reusing, budgeting, couponing, growing their own food, bartering, etc. From all accounts, they have healthy and happy lives. Second: If you take all other factors into consideration, even for those at the very bottom of the socio-economic scale, life is comparatively much better here. On average, people in the United States live 20–35 years longer than those in the Sub-Sahara. In America, there is an infant mortality rate of eight out of every 1,000. In Mali, the rate is 191 out of 1,000. While millions have perished in Africa because of famine, I have not been able to find any account of a single person starving to death in America because of an inability to acquire food. There are rare cases in which people are starved through abuse or neglect, but the issue of general access to food was not a factor. On the contrary, we are constantly reminded that we have an epidemic of obesity in our country. Looking at population statistics, this is a problem that affects the poor almost exclusively. Millions more have been butchered in war, slavery, and genocide in Africa during these past 20 years. With the exception of 9/11, war, slavery, and genocide have killed exactly nobody in America — unless you count the “War on Drugs.” (I’m excluding here our military adventures overseas — which both liberals and conservatives love — and focusing on civilian deaths within our borders. More than 1 million people die from AIDS/HIV in the Sub-Sahara each year. Nearly 2 million more contract the disease yearly. The region accounts for about 14 percent of the world’s population and 67 percent of all people living with HIV and 72 percent of all AIDS deaths in 2009. Contrast that to the United States, where there are approximately 1 million people infected with HIV. About 56,000 new people become infected each year, while roughly 18,000 per year die from AIDS. Even the poorest of poor in America have the means and ability to protect themselves from sexually transmitted diseases that ravish other populations. This represents just a cursory look over publicly available data, of course, but many inferences can be drawn. Living off $1,000 per year in the United States is actually a lot easier than living off of $1,000 per year in the Sub-Sahara. In the United States, $1,000 per year still makes you pretty well off compared to a huge majority of the world’s population. Instead of the OWS asking why this is the case (different economic and political policies have different economic and political outcomes), they are insisting that it’s not the case, in the face of all empirical evidence. It’s a complete break with reality. All of this begs a basic question. We know that there are millions of people living in Africa on $1,000 per year or less, but are there people living on $1,000 per year in America? Maybe. According to the 2008 United States Census, the number of individuals living on $2,500 or less is 12,945. If you count households instead of individuals, that number drops to about 3,000. Looking at demographics, we find that many of those either live on Indian reservations or in closed off religious communities. The vast majority live in very rural areas, with the exception of some communities in Texas and California. This brings up another awkward question. Can we differentiate between the worthy and the unworthy poor? Is it safe to say that those living on an Indian reservation are most likely the victims of centuries of oppression, paternalism, and other factors beyond their control, and deserve our sympathies, while those whose religious doctrines call for unsustainable familial and community growth (though still collecting welfare entitlements) don’t? Back to the original point. Taking this all into consideration, the speaker (along with 70 million of his fellow human beings) is more than likely in the top 1 percent of income earners in the world. Does he produce nothing? Do the other 70 million people produce nothing? If he had a shred of intellectual honesty, he would advocate taxing anyone who makes $34,000 per year or more at a very high rate so that money can be redistributed to the absolute poor in Africa, India, China, Afghanistan, etc. If you’re going to advocate forced redistribution, what’s the more moral course of action? Paying off student loan debt and making secondary education free for those who are extraordinarily rich in comparison to world standards, therefore giving them further opportunities to collect more wealth, or giving that money to someone who will quite literally starve to death without it?

Even though you can tell he’s searching for the concept, what he’s attempting to recall is the Labor Theory of Value, which suggests that the value of goods derives from their labor inputs. Some take it a step further and suggest that goods should therefore be priced according to those labor inputs rather than in response to the demand for those products. This murderous idea has been refuted too many times to count and isn’t taken seriously by mainstream economists. As with the devastating yet simple argument against Pascal’s Wager, this is a case of rudimentary logic pitted against religious thinking. If a laborer labors all day making mud pies instead of pumpkin pies, he may well have put in a great deal of work, but still produces absolutely nothing of value. Not understanding why someone would do that, I come along with a novel idea. Why not hire that labor (which is obviously motivated to work) and have him make pumpkin pies instead? Which is more valuable, the labor or the idea that moved the labor in a profitable direction? Given time, one of my workers gets a workable idea that it will actually make it more time- and cost-efficient to divide the labor and go into business for himself making ready-made pie crusts to sell back to me. In turn, he hires 10 more people. Another person figures out that growing local pumpkins for production is not sustainable or efficient, so he saves his capital and starts an import business to buy pumpkins to sell back to me. In turn, he hires 10 more people. Of course, that import company creates demand from pumpkin farmers halfway across the country, signaling to them that they need to hire more people. But what about packaging? How will I wrap all those pies? Where will I get the metal for pie tins? How do I even make a pie tin? What if I want to branch off into cherry pies or apple pies? What if I want to sell coffee with those pies? The Labor Theory of Value is an epic failure of imagination. At any given moment, there are two types of birds on the face of the earth, those that are airborne and those that are not. Do you know what the number of birds in each group will be, say, 10 seconds from now? The answer may well be impossible to ever figure out, but there is an answer as concrete and real as the computer screen you’re looking at. It will take a great deal of dispersed observation, knowledge, and computer power to ever figure out the answer to that question, but it takes an even greater amount of imagination to think of a use for the question in the first place. On the labor side of the equation, how many people per day, independent of each other, not even knowing of each other’s existence, were involved in making Steve Jobs’s ideas a reality? Can you imagine it? Can you even begin to try to imagine it? When you do, dig deeper. When you do that, dig deeper still. You will find yourself trying to comprehend a voluntary network of a number beyond your comprehension all working independently but in concert with each other in order to make that idea a reality. The vast majority have no earthly idea that they are working toward a common goal. If you’ve read the essay “I, Pencil,” you can start to grasp the amazing complexity of what goes into creating one simple product. Once you’ve started to grasp that concept, you realize that an iPhone or a Macbook is nearly infinitely more complex than a pencil. When you think you have a grasp on all of that, add into the mix all the competition that Steve Jobs inspired in the economy. Microsoft, Google, Android, Unix, Linux, smart phones, laptops, programming, software and hardware development, battery efficiency — the list goes on and on. Multiply everything above by factors unimaginable when you add in each new facet of competition. How many people were involved in making Steve Jobs’s ideas a reality? Like I said, there is a concrete answer to this question. I don’t doubt that computers will some day be able to figure it out. I’m not confident that it will ever happen in my lifetime. However, if you are able to imagine the several billion neurons in your brain exchanging countless bits of information each second, culminating in what we call human consciousness, then you are getting close to the complexity involved in the network of voluntary exchange Steve Jobs helped put into motion. Now think of the consumer side of the equation. For the purpose of this example, let’s limit ourselves to the latest model iPhone. For about $199, plus a two year contract with a cellular phone company, you can walk out the door with an iPhone 4S. Putting aside for a moment all the apps you can use, these are the features that come built in, off the shelf:

Another exercise in imagination, if you will: Consider every bit of technology listed above (we will ignore the wonderful advances in lithium battery, sensor, and storage technology for the purposes of this exercise) and the infrastructure needed for it to work. Now take it back in time just 20 years, to 1991. Keep in mind, all of this wonderful technology is crammed into 4.5 by 3.11 by 0.37 inches, with a total weight of 4.9 ounces. How much would something with comparable functionality cost back then? The logical answer would be that the technology did not exist 20 years ago, so it would be priceless. But this is a thought exercise, so we can at least break down some of the components and price them individually. In 1991, the most common portable analog phone (cell phone technology was still in its nascent stages) was a Motorola MicroTac 9800X. It was lauded for its compact size, and for being the first flip phone on the market. It was an inch thick and nine inches long (when opened), and weighed close to a pound. The only thing it did was make phone calls. The quality of the calls were reportedly pretty bad. You couldn’t use the phone while traveling outside your metropolitan area, and it was pricey to make any phone call. It sold for anywhere between $4,153 and $5,822 in current dollars (adjusted for inflation). The first digital camera was released in 1991. It was a Kodak Digital Camera System, and had a resolution of 1.3 megapixels. It also came with a 200 MB hard drive that could store about 160 uncompressed images. The hard drive and batteries had to be tethered to the camera by a cable. Cost in current dollars, adjusted for inflation: $33,317. This is where I stopped. At just two laughingly inefficient components (according to today’s standards; back then, they were miracles of technology) in comparison to what comes standard on any iPhone available for $199, I was already hovering around an overall price of $40,000. Extrapolate all of that out, including all the infrastructure required to make it work, and you can easily conclude that literally all the money in the world in 1991 could not buy you an iPhone. Today, I can walk into a store conveniently located near me and get a device that makes it nearly impossible for me to get lost, lets me communicate with people I’ve known my whole life who are scattered all over the globe, allows me to take wonderful pictures and record moments of my life, provides access to all the information available on the Internet, streams any number of movies or TV shows directly to me, tells me an extended forcast, lets me video chat with my daughters and phone anyone I wish, along with any number of other things — all for the paltry sum of $199 and the price of a two-year contract. A product that Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, the Queen of England, and any royal prince would be unable to purchase 20 years ago is now as ubiquitous as the air we breathe. That’s what Steve Jobs produced. And, as a bonus, the wealth created by his idea provided the means to countless other people around the world to purchase what he produced.

This pretty much speaks for itself. In this guy’s preferred system that disallows voluntary economic association, in order to get from point A to point B, a whole lot of murder, mayhem, theft, and rape will have to occur first with an end result of abject poverty for hundreds of millions of people.

There’s quite a bit of political philosophy that can be addressed here, but the next question pretty much sums it up for me.

This is a brilliant rejoinder. Popular democracy is nothing more than mob action. If everything is up for a vote and decidable by the “will of the people,” then there can be no individual rights, ever. The individual will always lose. The argument I often hear in support of popular democracy goes a little something like this: Wouldn’t you vote against Hitler to keep him out of power? Well, the very fact that someone like Hitler can run for an election tells me that the system is completely invalid. If the election is deemed valid and workable because he weren’t voted in, it would be just as valid and workable if he were voted in. That’s the long answer. The short answer is, “No, but I’d gladly shoot him in the face.” Even the OWS crowd seems to understand that popular democracy is basically the rule of the mob, because they have set up rules in their assemblies dictating that 100 percent consensus must be reached before anything passes. But that just makes the mob smaller.

An argument from belief is a religious argument. Also, framing an argument based on what you think that other people “need” is highly paternalistic. At worst, if carried out to its logical conclusion, this line of thought is murderous, if not genocidal. What is not acknowledged or understood here is the notion that a person’s talents and particular genius are priceless. A person’s talent and particular genius is nearly the whole sum of a person. Disallow a person to use his talents or genius in voluntary association with others, and you’ve essentially murdered his spirit. You’ve destroyed the greatest resource on the face of the earth, and it can never be replaced. Ever.

I’ve already eviscerated this notion above. It obviously does work. It obviously does not create mass unemployment or poverty. It obviously does not create war. In three minutes time, this person said he would do the following if he were in power:

None of this can be done without a whole lot of guns and a whole lot of cold-blooded murder. And in his mind, Steve Jobs creates war, poverty, and unemployment? I’ll just put these few examples here.

Combined with all other genocides, wars, famine and repression caused by national governments, the death toll for the 20th century is approximately 160 million. If you took half of the population of the United States (every other man, woman, and child) and shot them in the head, you would have the number of people murdered by governments, the majority of whom were killed by their own governments.

Of those 160 million murdered, how many may have turned out to be like Norman Borlaug, the man credited with saving up to 1 billion people worldwide from starvation? For those of you counting, that’s one seventh of the world’s current population. Can one honestly confront that number and still insist that talent and genius are not important? That free association should be done away with? That mob rule should prevail?

As Billy Beck brilliantly said when he linked to this video on Facebook, “Have you ever seen a man cut his own throat with philosophy?” Well, dear reader, you just have. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Corporatism, Economic Theory, Efficiency, Gains From Trade, Labor, Market Efficiency, Philosophy, Property Rights, Regulation, Rhetoric, Taxes, Trade, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 7:45 pm on October 20, 2011, by Justin M. Stoddard

The rich on Wall Street are demanding more bailouts:

Wait, you didn’t think I was talking about corporate bailouts, did you? No, I’m talking about the rich people who make up the Working Group of Occupy Wall Street. There is a very inconvenient and awkward question that is not being answered by the OWS crowd, as it pertains to wealth. Even making the assumption that the majority of those protesting are lower-middle class (a very liberal assumption, by anecdotal evidence), that would still mean that they are richer than 80 to 90 percent of the world’s population. In fact, the poorest 5 percent of the United States is still richer than 68 percent of the world’s population. When compared to the poorest in India, China, or Afghanistan, the inequality is breathtakingly staggering. That college kid who is 60 grand in debt may as well be Bill Gates to a girl born in parts of rural China or Afghanistan. Whenever this is brought up, you will inevitably hear this as a riposte:

In other words, you cannot ignore what is bad here because things are worse elsewhere. Well, that statement may well have merit, were it argued in another context. In this context, it is meaningless. Here’s why. The above “demands” have everything to do with trying to bring the classes to a parity rather than fixing the economy. We are constantly barraged with the 99 percent vs. the 1 percent rhetoric. This, in itself is a lie. At worst, the people protesting on Wall Street are the 32 percent. More likely, they are the 20 percent and up. If there were one shred of intellectual honesty in this movement, the above demands would be much, much different. They would be calling for taxing everyone in America at a much higher rate and redistributing that money to the poor in China and India. As the holders of 20 percent of the world’s wealth, they surely can afford it. After all, there are millions upon millions of people living in soul-crushing, abject poverty at this very moment. A vast number of them can never hope to make more than $1 per day, if that. Instead, we get demands for free education and free housing for all (well, for all the rich people living in the United States, anyway — everyone else can go get stuffed). This is nothing more than the rich seeking taxpayer money for bailouts through the use of force. Sound familiar? I’m not being flippant, here. When it comes to entitlements, tariffs, trade barriers, immigration or where I purchase my goods, I’ve not yet heard a convincing argument for why I should regard a middle-class or working poor American in any higher regard than the absolute poor of other countries. When I’m told that I should buy American in order to save American jobs, I wonder why a South Korean’s job is of any less importance. When I’m told that I must pay my fair share to help the deserving and undeserving (relatively) poor of this country, I wonder why the absolute poor from other countries shouldn’t get that money first. But this is what it’s come to, now. Rich college-age kids asking for taxpayer funded bailouts in order to relieve them of a debt (paid by the taxpayers) that they voluntarily took on with full knowledge that they would have to pay it back. Not only that, the vast majority of them have the means to pay off said debt through hard word and dedication. Now, tell me again why I should care that a rich kid got a liberal arts degree that didn’t pan out, when tens of millions are living in absolute poverty around the world. Tell me again why rich kids with liberal arts degrees aren’t sacrificing their income, well-being, and happiness to redistribute their wealth to those more in need. It’s time that we stopped focusing on this murderous idea of “inequality” when we should be thinking instead of relative standards of living over time. Maybe then we can focus on what’s wrong with our economy rather than just fight about which rich group of people get which bailouts. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Government Spending, Labor, Politics, Taxes, Trade Comments: 3 Comments

|

|

Posted at 12:05 am on October 19, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

Here’s a great cartoon from Completely Serious Comics published earlier this year, currently being passed around on Facebook by critics of Keynesian stimulus: I doubt the cartoon’s creators were thinking about government stimulus of aggregate demand when they conceived this, so it has become a piece of appropriated satire. And, like pretty much all great satire, it doesn’t play completely fair with its target. Even so, it contains a substantial nugget of truth. Readers of this blog who are familiar with the book from which it takes its name will be well-acquainted with the broken window fallacy, first created as a parable by Frédéric Bastiat and later appropriated by Henry Hazlitt, who applied it to a mid–20th century economy. In a nutshell, the parable explains why destruction doesn’t make a society wealthier. It may stimulate short-run economic activity as people rush to replace and rebuild what they’ve lost, but always at the expense of overall prosperity. Within the past few years, Bastiat’s and Hazlitt’s critical heirs have applied the fallacy again and again to modern Keynesians. Here’s a video that does exactly that to Paul Krugman’s application of Keynesian theory to the destruction wrought by terrorist attacks (featured on this blog last year): One objection to this line of thought could be that the broken window parable doesn’t apply to general stimulus, because government spending absent a disaster isn’t the same thing as destruction, and so isn’t analogous with a broken window. One response to this objection would be that the broken window parable is part of a larger essay about the unseen effects of various types of economic action. People explaining the arguments in the larger essay, which does indeed include government spending, might reasonably refer to them by invoking the best-known portion of that essay, the parable of the broken window. Conjuring the whole of an essay by referring to one part would be a kind of allegorical synecdoche, if you will. Another response would be that spending may not destroy useful physical objects, true enough, but it does divert resources from more productive to less productive uses. Although private-sector businesses can’t be sure what their most productive potential investment will be, the government is by nature even less informed and therefore less capable of investing wisely. Siphoning resources from the private sector to the public sector destroys wealth, even if it doesn’t destroy specific goods. An allegory of a destroyed object certainly applies to the reality of destroyed wealth. Keynesian apologists, and even some non-Keynesians, have cried foul in still more nuanced ways, pointing out that advocates of government stimulus don’t per se want destruction, and may not even think it will bring increased wealth, but think instead that it will increase short-term economic activity, increasing employment and smoothing over economically troubled times. There are indeed shades of meaning and intent here. Believing that destruction may benefit the economy in some structural way, thereby sustaining short-term damage for long-term gain, isn’t the same thing as thinking that any individual act of destruction will increase economic wealth. After all, as Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, entrepreneurs engage in short-term “creative” destruction all the time, writing off temporary losses as a necessary cost of pursuing their visions for long-term productive investment. The evidence, however, shows that government spending intended to stimulate the economy and smooth out the business cycle instead exacerbates the business cycle, leading both to higher peaks and lower valleys. As Russ Roberts pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

When there’s a downturn in the business cycle, there’s a structural problem with the economy — too many people in some occupations, not enough people in others. General stimulus provides no economic information about where people should go to find sustainable productive work, meeting real demands by providing the goods and services that people want rather than the trumped-up illusory demand prompted by government spending. You can’t build a healthy body on a string of sugar rushes, and you can’t build a healthy economy on a series of artificial top-down influxes of cash. Stimulus only spurs some sectors of the economy by dampening others, whether present or future. The more that government officials tamper with the economic signals that let entrepreneurs know when they should invest and when they should steer clear, the more skittish investors become. Regime uncertainty entrenches malinvestment, and keeps the economy limping along. So, Keynesians, please stop celebrating destruction as a cure for economic ills. If truly creative destruction needs to happen in order to move less productive resources into more productive uses, private-sector entrepreneurs have the decentralized knowledge necessary to determine which of their own resources need to be replaced or reshuffled. Government officials do not. The only real cure for our lagging economy is for the government to quit breaking windows. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 1:43 am on August 9, 2011, by David M. Brown

Let’s attempt the program of “economic stimulus” on a desert island. Five persons have survived the shipwreck. Joe is good at gathering berries and reeds, and dressing wounds; Al is good at fishing, hunting and basket-weaving; Bob is good at making huts and gourd-bowls; and Sam, who wants to spend all his time sharpening sticks, and who regards any other kind of employment as beneath him, cannot produce a tool of any usefulness. Let more and more of the resources that would have been exchanged in life-fostering and productivity-fostering trade between Joe, Al and Bob be confiscated by a fifth person, the king (who happens to have the only gun, a Kalashnikov that he grabbed from the ship before it crashed; elsewise no one would listen to him). And let this confiscated wealth (after a suitably large finder’s fee for the king has been deducted) be given to Sam to subsidize his slow and pointless blunt-stick production, since it would allegedly be unacceptable for Sam to have to accept alms in accordance with the sympathies and judgments of his fellows. And let the king perpetually demand more and more “revenue” to distribute and perpetually bray that criticism of his taxing and spending policies by “economic terrorists” is undermining confidence in the island’s economy. What are the effects of this confiscatory and redistributive process on the prospects for the islanders’ survival? Discuss. Filed under: Culture, Economic Theory, Efficiency, Finance, Food Policy, Gains From Trade, Government Spending, Health Care, Labor, Law Enforcement, Local Government, Market Efficiency, Nanny State, Philosophy, Politics, Property Rights, Taxes, Trade, Unintended Consequences Comments: Comments Off on What if there were deficit thinking, thinking deficit, on a desert island?

|

| Next Page » | previous posts » |

When I was a kid, I loved watching

When I was a kid, I loved watching

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."