|

Posted at 12:10 am on December 10, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

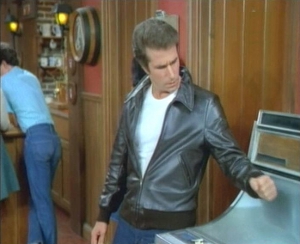

The Fonz could knock down doors with a slap of his hand, summon any girl with a snap, and most often on the show displayed his classic power of fixing the jukebox by banging on it. It’s a seductive fantasy that one might be able to fix a complex piece of machinery through an application of blunt force, without having to worry about the intricate mechanisms that actually allow the machine to work. Unfortunately, this is the mentality that has reigned for decades in applied public policy. Is the economy broken? Bang on it. That’ll get it chugging along again. Wait, that didn’t work? You didn’t bang it hard enough. Or maybe your leather jacket needs to be a little cooler next time. At any rate, it’s your fault. If you’d only smacked the economy the way that Fonzie showed you, it totally would have worked. Economic prescriptions thereby stem from a non-falsifiable tenet of faith in a grown-up power fantasy. This kind of magical thinking convinces many because it is accompanied by a veneer of rigorous thought. There are even equations! Surely, equations are scientific! But as economist Don Boudreaux pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

Keynesian macroeconomic variables lump heterogeneous goods and services into undifferentiated masses, no longer to be understood as the complex workings of a dynamic system of social cooperation. But just because you can gather a bunch of statistics and aggregate them into a variable doesn’t mean that the variable has a meaningful application to the real economy. If you want to fix a jukebox in real life, a mechanic might be able to get the job done by tinkering with the machinery until each piece once again functions correctly. It’s easy for people who have a facility with physical forms of engineering to take a similar view of the economy, thinking that if only the right people were in charge, they could tweak policy here and there to ensure successful outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith explained why the economy can’t be successfully engineered in such a way:

Even though an economy can’t be planned, or even tailored, successfully from on high, that form of scientism is at least understandable. It at least takes into account a small measure of the complexity of decentralized economic activity, even if it doesn’t — indeed, can’t — consider the rest. Keynesian macroeconomics is far worse, shunning even the scientistic attempt to grapple with at least some heterogeneous microeconomic factors as being the causal source of economywide trends. Instead, they insist that policymakers expropriate as much cash as humanly possible and wallop the economy with it as hard as they can. Economist Steven Horwitz summed up the real prescription for economic recovery:

In the end, the economy is not a jukebox, and neither a mechanic nor Ben Bernanke in the coolest leather jacket ever made can save it from its turmoils. Instead, the economy is made up of hundreds of millions of people with billions of plans, many of which fail but some of which succeed. Nobody knows for sure which plans will pan out in advance — not the people making them, and certainly not their public officials. Only by letting individuals, alone or in voluntary association with others, respond to local conditions with unique knowledge can the best plans be discovered, expanded, and replicated. That process is made much more difficult when they face continual interference from central planners who only pretend they can know what’s best. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 9:42 pm on December 1, 2011, by Wirkman Virkkala

The good folks at Coca-Cola really want to innovate. They probably admire the late Steve Jobs. They’ve lots of neat ideas. Helping polar bears is one of them. So, to honor the polar bears (or at least ballyhoo their cause and plight), Coke folk changed the color of the can of their main product, Coca-Cola™. They made it white. You know, “polar” color. And then came the uproar. Coke buyers didn’t like it. Many returned the product, thinking that it was either Diet Coke (whose silver can is, actually, very similar to the new white can) or else a modified product. A few Coke drinkers said that the drink tasted different. There was general confusion, as reported in the Wall Street Journal:

Obviously, this is another innovation from Coca-Cola that didn’t take – reminiscent of the infamous “New Coke” of a few decades ago. Coca-Cola’s clientele was so negative that the august Atlanta company switched plans, and is now switching back to the red cans we all know and love, far ahead of schedule. A lesson for us all. Consumers are sovereign. You can innovate up and down your line, but if consumers aren’t buying, you aren’t selling. The doctrine of consumer sovereignty was defended, in the 20th century, by two curmudgeonly economists, W.H. Hutt and Ludwig von Mises. The word choice was spot-on. “Consumers are sovereign” doesn’t mean that producers are meaningless. But the sovereign(s) have the last word, it’s the sovereign who must be pleased. And that’s what capitalism is all about. This lesson is probably hard on the innovators at Coca-Cola. Take the lame ending of that Wall Street Journal article:

Yes. But not distinct enough. And besides, the customer is always right. Well, right in the one way that matters most on the market, right in being sovereign. Note: I’m quite aware that the concept of consumer sovereignty is a metaphor, really, and not a technically pristine term. It was introduced by Hutt and Mises to counteract the nonsense now once again popular, the idea that corporations “push” us to do things against our will. This is patent nonsense, at least when it applies to the trades we make, the things we buy. We are pulled by producers, yes. But not pushed. We have the means to object. We can take our money elsewhere. We can simply not buy the product. As proven, once again, by the folks who drink Coke. Filed under: Economic Theory Comments: Comments Off on Coke Buyers Are Sovereign

|

When I was a kid, I loved watching

When I was a kid, I loved watching

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."