|

Posted at 12:10 am on December 10, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

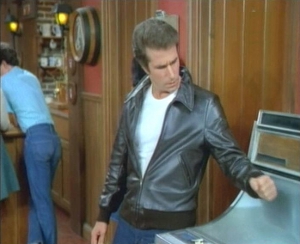

The Fonz could knock down doors with a slap of his hand, summon any girl with a snap, and most often on the show displayed his classic power of fixing the jukebox by banging on it. It’s a seductive fantasy that one might be able to fix a complex piece of machinery through an application of blunt force, without having to worry about the intricate mechanisms that actually allow the machine to work. Unfortunately, this is the mentality that has reigned for decades in applied public policy. Is the economy broken? Bang on it. That’ll get it chugging along again. Wait, that didn’t work? You didn’t bang it hard enough. Or maybe your leather jacket needs to be a little cooler next time. At any rate, it’s your fault. If you’d only smacked the economy the way that Fonzie showed you, it totally would have worked. Economic prescriptions thereby stem from a non-falsifiable tenet of faith in a grown-up power fantasy. This kind of magical thinking convinces many because it is accompanied by a veneer of rigorous thought. There are even equations! Surely, equations are scientific! But as economist Don Boudreaux pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

Keynesian macroeconomic variables lump heterogeneous goods and services into undifferentiated masses, no longer to be understood as the complex workings of a dynamic system of social cooperation. But just because you can gather a bunch of statistics and aggregate them into a variable doesn’t mean that the variable has a meaningful application to the real economy. If you want to fix a jukebox in real life, a mechanic might be able to get the job done by tinkering with the machinery until each piece once again functions correctly. It’s easy for people who have a facility with physical forms of engineering to take a similar view of the economy, thinking that if only the right people were in charge, they could tweak policy here and there to ensure successful outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith explained why the economy can’t be successfully engineered in such a way:

Even though an economy can’t be planned, or even tailored, successfully from on high, that form of scientism is at least understandable. It at least takes into account a small measure of the complexity of decentralized economic activity, even if it doesn’t — indeed, can’t — consider the rest. Keynesian macroeconomics is far worse, shunning even the scientistic attempt to grapple with at least some heterogeneous microeconomic factors as being the causal source of economywide trends. Instead, they insist that policymakers expropriate as much cash as humanly possible and wallop the economy with it as hard as they can. Economist Steven Horwitz summed up the real prescription for economic recovery:

In the end, the economy is not a jukebox, and neither a mechanic nor Ben Bernanke in the coolest leather jacket ever made can save it from its turmoils. Instead, the economy is made up of hundreds of millions of people with billions of plans, many of which fail but some of which succeed. Nobody knows for sure which plans will pan out in advance — not the people making them, and certainly not their public officials. Only by letting individuals, alone or in voluntary association with others, respond to local conditions with unique knowledge can the best plans be discovered, expanded, and replicated. That process is made much more difficult when they face continual interference from central planners who only pretend they can know what’s best. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 10:30 am on November 6, 2011, by Justin M. Stoddard

First, allow me to clarify a few points about the video below before I start into the meat of the matter. The video is obviously edited — for what purpose, I do not know. It could have been to cut down its length or to stitch together a narrative that puts the person being interviewed in the worst possible light. Though, admittedly, given his statements, I don’t know how that’s possible. I understand that people who are put on the spot with a camera in front of their face are going to stammer and search for words. After seeing thousands of these kinds of videos, I’m convinced that people generally do not do well when confronted with on-the-spot interviews.

There are some awkward questions that need to be asked in response to this assertion. Besides the obvious catchy “one percent of the people own 43 percent of the wealth” trope, why not move that arbitrary line to the top five percent? If the top one percent own 43 percent of the wealth, wouldn’t it follow that the top five percent own even more of the wealth? How about the top ten percent? The top 25 percent? The arbitrary line is chosen because it fits nicely into the idea of the proletariat struggling against the bourgeois. What is being insinuated here is the top one percent own the means of production while the 99% are the factors of production. How is the “1 percent” being defined here? One percent of the population of the United States or of the population of the world? The question matters a great deal, for a couple of reasons: One percent of the population of the United States is a little more than 3 million people (approximately the population of Mississippi). Just playing the numbers game, it strains all credulity to accept the assertion that the more than 3 million people being referenced here don’t produce anything. One percent of the world’s population is about 70 million people (approximately the population of California, New York, and Ohio combined). Of course, this takes credulity to the breaking point. The question hardly needed to be asked. The only population statistic being used here is the population of the United States. The OWS crowd skirts over the fact that if they were to count the entire population of world, the majority of them would end up in the top 1 percent of people who control wealth. That’s simply an argument they dare not broach. I’ve addressed this briefly here, but I’ll expound on it just a bit. Even adjusting for purchasing power parity, if you make $34,000 or more per year, you are in the top 1 percent of world income earners. Income disparity between someone who makes $34,000 and someone who makes $500,000 per year in the United States seems pretty significant, but not nearly as significant as the income disparity between someone who makes $34,000 per year in the United States and someone who makes $7,000 dollars per year in India, or $1,000 per year in Africa. The standard argument against this line of reasoning goes like this:

Lest I be accused of making up my own argument to refute, that’s a response I got on a recent Reddit thread addressing what I said above. At first blush, this makes quite a bit of sense. Commodities do seem to be more expensive in the United States than they are in the Sub-Sahara (unless you are living in a country with hyper-inflation). Earning $1,000 per year will certianly not give you the purchasing power to buy or rent a house or an apartment. You may or may not be able to afford transportation. Food and clothing would also be difficult to acquire. But, one is tempted to ask; would you rather live in the United States with an income of $1,000 per year or in Sub-Saharan Africa with an income of $1,000 per year? Here are the two main problems I see: First: The United States (and other First World countries) have many orders of magnitude more consumer goods and commodities to choose from than all of the Sub-Sahara put together. In the United States, $1,000 goes much further because there is so much more you can do with it. You must also consider basic welfare entitlements to every poor citizen in the United States to be used for food, shelter and clothing, along with other factors of income like child support payments and not being required to pay taxes. It further discounts the ability to barter for goods, rely on charity, and utilize the cast-offs of the rich and middle class. Our country is awash with high-class “junk.” It is very easy to acquire clothes, furniture, gadgets (TVs, microwaves, phones, radios, etc.) just by asking for it. It’s unbelievable how much stuff the well-off just leave on the curb for others to pick up. Whole virtual communities like Freecycle and Craigslist thrive around the concept of either exchanging these types of goods or just giving them away. If you are savvy enough, it is possible to get hundreds of dollars worth of name brand products for free through the practice of extreme couponing. There are literally hundreds of blogs dedicated to the concept of extreme frugality, meaning there are people in this country who choose to live well below the poverty line by recycling, reusing, budgeting, couponing, growing their own food, bartering, etc. From all accounts, they have healthy and happy lives. Second: If you take all other factors into consideration, even for those at the very bottom of the socio-economic scale, life is comparatively much better here. On average, people in the United States live 20–35 years longer than those in the Sub-Sahara. In America, there is an infant mortality rate of eight out of every 1,000. In Mali, the rate is 191 out of 1,000. While millions have perished in Africa because of famine, I have not been able to find any account of a single person starving to death in America because of an inability to acquire food. There are rare cases in which people are starved through abuse or neglect, but the issue of general access to food was not a factor. On the contrary, we are constantly reminded that we have an epidemic of obesity in our country. Looking at population statistics, this is a problem that affects the poor almost exclusively. Millions more have been butchered in war, slavery, and genocide in Africa during these past 20 years. With the exception of 9/11, war, slavery, and genocide have killed exactly nobody in America — unless you count the “War on Drugs.” (I’m excluding here our military adventures overseas — which both liberals and conservatives love — and focusing on civilian deaths within our borders. More than 1 million people die from AIDS/HIV in the Sub-Sahara each year. Nearly 2 million more contract the disease yearly. The region accounts for about 14 percent of the world’s population and 67 percent of all people living with HIV and 72 percent of all AIDS deaths in 2009. Contrast that to the United States, where there are approximately 1 million people infected with HIV. About 56,000 new people become infected each year, while roughly 18,000 per year die from AIDS. Even the poorest of poor in America have the means and ability to protect themselves from sexually transmitted diseases that ravish other populations. This represents just a cursory look over publicly available data, of course, but many inferences can be drawn. Living off $1,000 per year in the United States is actually a lot easier than living off of $1,000 per year in the Sub-Sahara. In the United States, $1,000 per year still makes you pretty well off compared to a huge majority of the world’s population. Instead of the OWS asking why this is the case (different economic and political policies have different economic and political outcomes), they are insisting that it’s not the case, in the face of all empirical evidence. It’s a complete break with reality. All of this begs a basic question. We know that there are millions of people living in Africa on $1,000 per year or less, but are there people living on $1,000 per year in America? Maybe. According to the 2008 United States Census, the number of individuals living on $2,500 or less is 12,945. If you count households instead of individuals, that number drops to about 3,000. Looking at demographics, we find that many of those either live on Indian reservations or in closed off religious communities. The vast majority live in very rural areas, with the exception of some communities in Texas and California. This brings up another awkward question. Can we differentiate between the worthy and the unworthy poor? Is it safe to say that those living on an Indian reservation are most likely the victims of centuries of oppression, paternalism, and other factors beyond their control, and deserve our sympathies, while those whose religious doctrines call for unsustainable familial and community growth (though still collecting welfare entitlements) don’t? Back to the original point. Taking this all into consideration, the speaker (along with 70 million of his fellow human beings) is more than likely in the top 1 percent of income earners in the world. Does he produce nothing? Do the other 70 million people produce nothing? If he had a shred of intellectual honesty, he would advocate taxing anyone who makes $34,000 per year or more at a very high rate so that money can be redistributed to the absolute poor in Africa, India, China, Afghanistan, etc. If you’re going to advocate forced redistribution, what’s the more moral course of action? Paying off student loan debt and making secondary education free for those who are extraordinarily rich in comparison to world standards, therefore giving them further opportunities to collect more wealth, or giving that money to someone who will quite literally starve to death without it?

Even though you can tell he’s searching for the concept, what he’s attempting to recall is the Labor Theory of Value, which suggests that the value of goods derives from their labor inputs. Some take it a step further and suggest that goods should therefore be priced according to those labor inputs rather than in response to the demand for those products. This murderous idea has been refuted too many times to count and isn’t taken seriously by mainstream economists. As with the devastating yet simple argument against Pascal’s Wager, this is a case of rudimentary logic pitted against religious thinking. If a laborer labors all day making mud pies instead of pumpkin pies, he may well have put in a great deal of work, but still produces absolutely nothing of value. Not understanding why someone would do that, I come along with a novel idea. Why not hire that labor (which is obviously motivated to work) and have him make pumpkin pies instead? Which is more valuable, the labor or the idea that moved the labor in a profitable direction? Given time, one of my workers gets a workable idea that it will actually make it more time- and cost-efficient to divide the labor and go into business for himself making ready-made pie crusts to sell back to me. In turn, he hires 10 more people. Another person figures out that growing local pumpkins for production is not sustainable or efficient, so he saves his capital and starts an import business to buy pumpkins to sell back to me. In turn, he hires 10 more people. Of course, that import company creates demand from pumpkin farmers halfway across the country, signaling to them that they need to hire more people. But what about packaging? How will I wrap all those pies? Where will I get the metal for pie tins? How do I even make a pie tin? What if I want to branch off into cherry pies or apple pies? What if I want to sell coffee with those pies? The Labor Theory of Value is an epic failure of imagination. At any given moment, there are two types of birds on the face of the earth, those that are airborne and those that are not. Do you know what the number of birds in each group will be, say, 10 seconds from now? The answer may well be impossible to ever figure out, but there is an answer as concrete and real as the computer screen you’re looking at. It will take a great deal of dispersed observation, knowledge, and computer power to ever figure out the answer to that question, but it takes an even greater amount of imagination to think of a use for the question in the first place. On the labor side of the equation, how many people per day, independent of each other, not even knowing of each other’s existence, were involved in making Steve Jobs’s ideas a reality? Can you imagine it? Can you even begin to try to imagine it? When you do, dig deeper. When you do that, dig deeper still. You will find yourself trying to comprehend a voluntary network of a number beyond your comprehension all working independently but in concert with each other in order to make that idea a reality. The vast majority have no earthly idea that they are working toward a common goal. If you’ve read the essay “I, Pencil,” you can start to grasp the amazing complexity of what goes into creating one simple product. Once you’ve started to grasp that concept, you realize that an iPhone or a Macbook is nearly infinitely more complex than a pencil. When you think you have a grasp on all of that, add into the mix all the competition that Steve Jobs inspired in the economy. Microsoft, Google, Android, Unix, Linux, smart phones, laptops, programming, software and hardware development, battery efficiency — the list goes on and on. Multiply everything above by factors unimaginable when you add in each new facet of competition. How many people were involved in making Steve Jobs’s ideas a reality? Like I said, there is a concrete answer to this question. I don’t doubt that computers will some day be able to figure it out. I’m not confident that it will ever happen in my lifetime. However, if you are able to imagine the several billion neurons in your brain exchanging countless bits of information each second, culminating in what we call human consciousness, then you are getting close to the complexity involved in the network of voluntary exchange Steve Jobs helped put into motion. Now think of the consumer side of the equation. For the purpose of this example, let’s limit ourselves to the latest model iPhone. For about $199, plus a two year contract with a cellular phone company, you can walk out the door with an iPhone 4S. Putting aside for a moment all the apps you can use, these are the features that come built in, off the shelf:

Another exercise in imagination, if you will: Consider every bit of technology listed above (we will ignore the wonderful advances in lithium battery, sensor, and storage technology for the purposes of this exercise) and the infrastructure needed for it to work. Now take it back in time just 20 years, to 1991. Keep in mind, all of this wonderful technology is crammed into 4.5 by 3.11 by 0.37 inches, with a total weight of 4.9 ounces. How much would something with comparable functionality cost back then? The logical answer would be that the technology did not exist 20 years ago, so it would be priceless. But this is a thought exercise, so we can at least break down some of the components and price them individually. In 1991, the most common portable analog phone (cell phone technology was still in its nascent stages) was a Motorola MicroTac 9800X. It was lauded for its compact size, and for being the first flip phone on the market. It was an inch thick and nine inches long (when opened), and weighed close to a pound. The only thing it did was make phone calls. The quality of the calls were reportedly pretty bad. You couldn’t use the phone while traveling outside your metropolitan area, and it was pricey to make any phone call. It sold for anywhere between $4,153 and $5,822 in current dollars (adjusted for inflation). The first digital camera was released in 1991. It was a Kodak Digital Camera System, and had a resolution of 1.3 megapixels. It also came with a 200 MB hard drive that could store about 160 uncompressed images. The hard drive and batteries had to be tethered to the camera by a cable. Cost in current dollars, adjusted for inflation: $33,317. This is where I stopped. At just two laughingly inefficient components (according to today’s standards; back then, they were miracles of technology) in comparison to what comes standard on any iPhone available for $199, I was already hovering around an overall price of $40,000. Extrapolate all of that out, including all the infrastructure required to make it work, and you can easily conclude that literally all the money in the world in 1991 could not buy you an iPhone. Today, I can walk into a store conveniently located near me and get a device that makes it nearly impossible for me to get lost, lets me communicate with people I’ve known my whole life who are scattered all over the globe, allows me to take wonderful pictures and record moments of my life, provides access to all the information available on the Internet, streams any number of movies or TV shows directly to me, tells me an extended forcast, lets me video chat with my daughters and phone anyone I wish, along with any number of other things — all for the paltry sum of $199 and the price of a two-year contract. A product that Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, the Queen of England, and any royal prince would be unable to purchase 20 years ago is now as ubiquitous as the air we breathe. That’s what Steve Jobs produced. And, as a bonus, the wealth created by his idea provided the means to countless other people around the world to purchase what he produced.

This pretty much speaks for itself. In this guy’s preferred system that disallows voluntary economic association, in order to get from point A to point B, a whole lot of murder, mayhem, theft, and rape will have to occur first with an end result of abject poverty for hundreds of millions of people.

There’s quite a bit of political philosophy that can be addressed here, but the next question pretty much sums it up for me.

This is a brilliant rejoinder. Popular democracy is nothing more than mob action. If everything is up for a vote and decidable by the “will of the people,” then there can be no individual rights, ever. The individual will always lose. The argument I often hear in support of popular democracy goes a little something like this: Wouldn’t you vote against Hitler to keep him out of power? Well, the very fact that someone like Hitler can run for an election tells me that the system is completely invalid. If the election is deemed valid and workable because he weren’t voted in, it would be just as valid and workable if he were voted in. That’s the long answer. The short answer is, “No, but I’d gladly shoot him in the face.” Even the OWS crowd seems to understand that popular democracy is basically the rule of the mob, because they have set up rules in their assemblies dictating that 100 percent consensus must be reached before anything passes. But that just makes the mob smaller.

An argument from belief is a religious argument. Also, framing an argument based on what you think that other people “need” is highly paternalistic. At worst, if carried out to its logical conclusion, this line of thought is murderous, if not genocidal. What is not acknowledged or understood here is the notion that a person’s talents and particular genius are priceless. A person’s talent and particular genius is nearly the whole sum of a person. Disallow a person to use his talents or genius in voluntary association with others, and you’ve essentially murdered his spirit. You’ve destroyed the greatest resource on the face of the earth, and it can never be replaced. Ever.

I’ve already eviscerated this notion above. It obviously does work. It obviously does not create mass unemployment or poverty. It obviously does not create war. In three minutes time, this person said he would do the following if he were in power:

None of this can be done without a whole lot of guns and a whole lot of cold-blooded murder. And in his mind, Steve Jobs creates war, poverty, and unemployment? I’ll just put these few examples here.

Combined with all other genocides, wars, famine and repression caused by national governments, the death toll for the 20th century is approximately 160 million. If you took half of the population of the United States (every other man, woman, and child) and shot them in the head, you would have the number of people murdered by governments, the majority of whom were killed by their own governments.

Of those 160 million murdered, how many may have turned out to be like Norman Borlaug, the man credited with saving up to 1 billion people worldwide from starvation? For those of you counting, that’s one seventh of the world’s current population. Can one honestly confront that number and still insist that talent and genius are not important? That free association should be done away with? That mob rule should prevail?

As Billy Beck brilliantly said when he linked to this video on Facebook, “Have you ever seen a man cut his own throat with philosophy?” Well, dear reader, you just have. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Corporatism, Economic Theory, Efficiency, Gains From Trade, Labor, Market Efficiency, Philosophy, Property Rights, Regulation, Rhetoric, Taxes, Trade, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 12:05 am on October 19, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

Here’s a great cartoon from Completely Serious Comics published earlier this year, currently being passed around on Facebook by critics of Keynesian stimulus: I doubt the cartoon’s creators were thinking about government stimulus of aggregate demand when they conceived this, so it has become a piece of appropriated satire. And, like pretty much all great satire, it doesn’t play completely fair with its target. Even so, it contains a substantial nugget of truth. Readers of this blog who are familiar with the book from which it takes its name will be well-acquainted with the broken window fallacy, first created as a parable by Frédéric Bastiat and later appropriated by Henry Hazlitt, who applied it to a mid–20th century economy. In a nutshell, the parable explains why destruction doesn’t make a society wealthier. It may stimulate short-run economic activity as people rush to replace and rebuild what they’ve lost, but always at the expense of overall prosperity. Within the past few years, Bastiat’s and Hazlitt’s critical heirs have applied the fallacy again and again to modern Keynesians. Here’s a video that does exactly that to Paul Krugman’s application of Keynesian theory to the destruction wrought by terrorist attacks (featured on this blog last year): One objection to this line of thought could be that the broken window parable doesn’t apply to general stimulus, because government spending absent a disaster isn’t the same thing as destruction, and so isn’t analogous with a broken window. One response to this objection would be that the broken window parable is part of a larger essay about the unseen effects of various types of economic action. People explaining the arguments in the larger essay, which does indeed include government spending, might reasonably refer to them by invoking the best-known portion of that essay, the parable of the broken window. Conjuring the whole of an essay by referring to one part would be a kind of allegorical synecdoche, if you will. Another response would be that spending may not destroy useful physical objects, true enough, but it does divert resources from more productive to less productive uses. Although private-sector businesses can’t be sure what their most productive potential investment will be, the government is by nature even less informed and therefore less capable of investing wisely. Siphoning resources from the private sector to the public sector destroys wealth, even if it doesn’t destroy specific goods. An allegory of a destroyed object certainly applies to the reality of destroyed wealth. Keynesian apologists, and even some non-Keynesians, have cried foul in still more nuanced ways, pointing out that advocates of government stimulus don’t per se want destruction, and may not even think it will bring increased wealth, but think instead that it will increase short-term economic activity, increasing employment and smoothing over economically troubled times. There are indeed shades of meaning and intent here. Believing that destruction may benefit the economy in some structural way, thereby sustaining short-term damage for long-term gain, isn’t the same thing as thinking that any individual act of destruction will increase economic wealth. After all, as Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, entrepreneurs engage in short-term “creative” destruction all the time, writing off temporary losses as a necessary cost of pursuing their visions for long-term productive investment. The evidence, however, shows that government spending intended to stimulate the economy and smooth out the business cycle instead exacerbates the business cycle, leading both to higher peaks and lower valleys. As Russ Roberts pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

When there’s a downturn in the business cycle, there’s a structural problem with the economy — too many people in some occupations, not enough people in others. General stimulus provides no economic information about where people should go to find sustainable productive work, meeting real demands by providing the goods and services that people want rather than the trumped-up illusory demand prompted by government spending. You can’t build a healthy body on a string of sugar rushes, and you can’t build a healthy economy on a series of artificial top-down influxes of cash. Stimulus only spurs some sectors of the economy by dampening others, whether present or future. The more that government officials tamper with the economic signals that let entrepreneurs know when they should invest and when they should steer clear, the more skittish investors become. Regime uncertainty entrenches malinvestment, and keeps the economy limping along. So, Keynesians, please stop celebrating destruction as a cure for economic ills. If truly creative destruction needs to happen in order to move less productive resources into more productive uses, private-sector entrepreneurs have the decentralized knowledge necessary to determine which of their own resources need to be replaced or reshuffled. Government officials do not. The only real cure for our lagging economy is for the government to quit breaking windows. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 1:43 am on August 9, 2011, by David M. Brown

Let’s attempt the program of “economic stimulus” on a desert island. Five persons have survived the shipwreck. Joe is good at gathering berries and reeds, and dressing wounds; Al is good at fishing, hunting and basket-weaving; Bob is good at making huts and gourd-bowls; and Sam, who wants to spend all his time sharpening sticks, and who regards any other kind of employment as beneath him, cannot produce a tool of any usefulness. Let more and more of the resources that would have been exchanged in life-fostering and productivity-fostering trade between Joe, Al and Bob be confiscated by a fifth person, the king (who happens to have the only gun, a Kalashnikov that he grabbed from the ship before it crashed; elsewise no one would listen to him). And let this confiscated wealth (after a suitably large finder’s fee for the king has been deducted) be given to Sam to subsidize his slow and pointless blunt-stick production, since it would allegedly be unacceptable for Sam to have to accept alms in accordance with the sympathies and judgments of his fellows. And let the king perpetually demand more and more “revenue” to distribute and perpetually bray that criticism of his taxing and spending policies by “economic terrorists” is undermining confidence in the island’s economy. What are the effects of this confiscatory and redistributive process on the prospects for the islanders’ survival? Discuss. Filed under: Culture, Economic Theory, Efficiency, Finance, Food Policy, Gains From Trade, Government Spending, Health Care, Labor, Law Enforcement, Local Government, Market Efficiency, Nanny State, Philosophy, Politics, Property Rights, Taxes, Trade, Unintended Consequences Comments: Comments Off on What if there were deficit thinking, thinking deficit, on a desert island?

|

|

Posted at 5:11 pm on June 19, 2011, by Sarah Brodsky

I was surprised by this post on Common Sense Concept, a blog published by the American Enterprise Institute. Although the author has written in support of private charity, in this post he argues that fairness in terms of material outcomes is not desirable. He supports this argument with quotations from various Christian texts and concludes by saying, “Let us be content with managing our own affairs”. I won’t address the religious justification for this position, but I’d like to point out that the author is overlooking several ways in which fairness matters for the free market. First, unfair outcomes such as poverty and economic immobility can be an indication that the market is not working so well as it should. This may be caused by government intervention or incompetence, as when centralized education policies trap poor children in schools that don’t prepare them to enter the workforce. Or it may be a sign of untapped opportunities, like the lack of access to banking services by residents of the central Amazon. Whether the solution is the curtailment of government power or entrepreneurial innovation, we should heed these instances of unfairness so that we can make the market better. Second, economic conditions change and the people who are privileged today could be needy tomorrow. We’ve all heard stories of people who lost their life savings in the latest recession; even in calmer economic times, giant corporations and once-profitable-looking investments can vanish as technology evolves. The existence of a safety net, possibly based on private charity, could give people the confidence to start new ventures and to take the risks necessary for innovation, knowing that their basic needs will be met if they fail. Charities should also ensure that the poorest people can survive without resorting to theft and crime, which can cripple a market system. The post’s author might counter that we should give charity without regard to fairness, but I don’t see how that’s possible. Do you give charity to the first wealthy person who walks by your door? Of course not. You look for the people who need charity the most–in short, the people in the least fair situations. Finally, I’d like to remind the author that we don’t have a free market with perfect efficiency. While based on the econ textbooks, one might think that demand for innovations will lead to an increase in the number and quality of innovators, in real life that doesn’t always happen. If the person who could have cured cancer or revolutionized communications was born into unfair circumstances, he might not obtain the necessary human capital investments through no fault of his own. That’s not just a tragedy for him. It makes the rest of us poorer too because we don’t get to benefit from his potential contribution to the economy. So while we shouldn’t count on government to smooth every inequity, we should give serious thought to fairness if we want a successful market. Filed under: Efficiency, Market Efficiency Comments: 2 Comments

|

|

Posted at 1:51 pm on May 3, 2010, by Caitlin Hartsell

Last week at a Liberty on the Rocks meeting, we discussed the need to show others how the market can provide for the disadvantaged better than the government can. Many libertarians may take this for granted, but this is a relatively important fact to establish in order to combat the idea that the government is necessary to help people. I thought I’d write a few posts on the topic of “the market at work” based off a few good examples I have recently encountered. (If anyone else has good examples to share, please do!) KickStart For the last three class periods in my Program Planning class, we have been discussing a case study of KickStart, a company that sells treadle pumps to farmers in Kenya, Mali and Tanzania. A treadle pump doesn’t need fossil fuels to extract groundwater, so it can efficiently provide large amounts of water. It can be a cost-effective method for farmers to increase their output so they can sell their produce. The Lessons Learned page on KickStart’s site is well worth reading in its entirety, but the main gist is that their founders were unsatisfied with the typical program model that focuses on giving away money or services, which has not been a lasting solution. What the poor need most is a way to make money; providing reliable and long-lasting tools are the best way to help them do that. It is the “teach a man to fish” idea. Increasing the standard of living of an entire country requires an increase in production. An influx of foreign aid–without a subsequent increase in production– will not raise the standard of living across the board. By creating a tool that will help farmers be more productive, KickStart can help people in a lasting manner. Essentially, KickStart‘s long-term idea is that “creating a middle class is the most sustainable way to lift a country out of poverty.” To do this, they have created a product that will help people become entrepreneurs. Using the market KickStart is different from many similar organizations because it believes that selling their products is better than giving them away. There is an elaborate chart that explains how, because they sell the products, they are able to help three times the number of people than if they gave them away. By commodifying the product, there is a profit motive that incentivizes each portion of the supply chain to become more efficient. Even if the donor funds disappear, people will still be able to get pumps. Most importantly, the price system also allocates the products more efficiently than giving them away. When people have to make an investment, they are more likely to actually use them to create their own enterprise. The pump makers are accountable to create pumps that fit the needs of their usersr. Because KickStart sells the product, there is a self-sustaining supply chain that keeps costs low and allows people to fix the product when a part breaks. The Ethics of Selling? One complaint my class had was that it was “unethical” to sell these treadle pumps because selling exacerbates socioeconomic differences, since those that can afford the pump may be slightly better off already. Inequity is a hot topic issue in many of my classes. While inequity is a problem, I think that the focus should be more on how low the bottom is, as opposed to how different the bottom is from the top. Helping people up from the bottom should always be seen as a good. But the part that is missed is the effect that something like a treadle pump can have on an entire community. When a few people are able to raise their standard of living, more money is brought into the community. This money is spent on other businesses in the region, which can benefits other people, whether or not they purchases a pump. Also, the “early adopters” help establish the supply chain and find any “bugs” within the product. Over time, the supply chain and technology will improve both the efficacy of the pumps and their cost, allowing other people to buy the pumps. These market forces have been seen in many products; by selling the pump, the proper incentive structure is set up to improve the pump and to determine the method to provide it in the cheapest manner possible. When one looks at KickStart’s data showing that they can help three times the number of people by selling instead of giving the product away, it seems unethical to not sell the pumps. Their Success How successful has KickStart been? We’ll find out after the pending independent evaluation, but the anecdotes seem to show that it has made great strides for many involved. According to their own measures, they have sold 144,600 pumps, helped create 93,200 enterprises, helped 466,000 people out of poverty and generated $94 million in new wages, which is fifteen times the amount of donor funds. This means it took about $60 to get one person out of poverty. Whether or not these results are overestimated, it is still an impressive impact from one organization. Most importantly though, KickStart is affecting real, cost-effective change that doesn’t rely on government intervention. Emulating and promoting their model elsewhere is one way to show people how the market is the best mechanism to really help people. Filed under: Economic Theory, Market Efficiency Comments: 2 Comments

|

|

Posted at 12:04 am on April 19, 2010, by John W. Payne

The left wing caricature of a market economy presents rapacious businessmen monopolizing resources and raising prices to further enrich the wealthy while crushing the poor and middle class. There are a multitude of problems with this notion, but the primary one is that the market almost always discourages monopoly and drives prices down for the benefit of everyone except the firms that cannot compete. Even more remarkable is that in many cases the downward pressure on prices actually reaches its logical conclusion of firms giving away numerous goods and services for free (i.e. at a zero monetary cost to consumers). One often overlooked example of this phenomenon is the near total availability of condiments at fast food restaurants. Salt, pepper, ketchup, mustard, hot sauce, and more can be taken in large amounts whenever you make an order. When I was still in college, I stockpiled those little packets to use at home so that I didn’t have to pay for them at the grocery store. I’m sure this seems insignificant to most people, but that’s only because the market has made these goods so abundant that we take them for granted. In ages past, salt was such a valuable commodity that it was used as money, giving rise to the expression “worth your salt.” And it was demand for other spices like pepper that sent Europeans scrambling across the world 500 years ago in an effort to reap the enormous profits they could bring. It is nothing short of amazing that what was once so expensive that thousands of people would risk their lives to procure it is now so abundant that we don’t even give a second thought to people giving it away. A similar, if more high tech, example of the same phenomenon is the plethora of restaurants and coffee shops that now give away free WiFi internet access to anyone who wants it. Most of these places don’t even require users to make a purchase, operating on the belief that the longer a person stays in the store, the more likely they are to buy something. If you have a laptop, you can now access the greatest store of information the world has ever known as much as you want for free, all thanks to the free market, which forces businesses to compete by enticing potential customers with such fringe benefits. You might object here that the cost of these goods is included in the price of a meal, so it isn’t actually free to the consumer. That cost is negligible, which is why they give the stuff away, but the point is true enough, so let me give you a few examples where the user never has to spend a dime to reap some pretty enormous benefits. Many of the internet’s most powerful tools are completely free to users. Without search engines, the internet would be of very limited use, but despite being so valuable, they are almost all free because if one tried to charge people would very quickly migrate to a free alternative. Facebook allows individuals, businesses, charities, and all other manner of like-minded groups to set up free profiles and communicate with each other. I regularly chat on Facebook with friends across the country and the globe. Two generations ago, such instant communication wasn’t available at any price, but now it’s just part of an average day. The major search engines and Facebook rely on advertisers to provide their revenue, so you only pay for those services if you buy something through one of their ads. Furthermore, even these ads typically benefit the consumers. Because the advertisements are generated by a computer program based on information given by the user, they are more likely to be of interest than the average TV or radio commercial, and if a person buys a product because of the ad, he is made better off, provided it meets his expectations. To give a personal example, I discovered the service Groupon, which sells daily coupons to local businesses with steep discounts, through an ad on Facebook. I have eaten numerous meals for around 50 percent off thanks to Facebook, a service that I enjoy for free. Now contrast these remarkable market achievements with the government. The free market is providing numerous, highly valued goods and services at no cost to the consumer. On the other hand, the government provides many “services” that I don’t even want (e.g. the drug war, the war in Iraq, illegal wiretapping) and never for free. Why anyone would ever prefer the latter to the former is beyond me. Filed under: Economic Theory, Market Efficiency Comments: 7 Comments

|

|

Posted at 7:30 pm on April 16, 2010, by Christine Harbin

As component of its Make a Difference campaign, Starbucks gives its customers a 10 cent discount if they use a reusable travel mug. This is another example of how the private sector can encourage certain behaviors without direction from the government, such as environmental stewardship. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives like Starbucks’s are preferable to government mandates because they respect individual choice. If, for whatever reason, a person does not want to use a reusable mug, he or she can still purchase coffee. Consumers win because they pay a lower price for the product and also because their choice is unrestricted. Companies like Starbucks win because they can reduce their material and inventory costs. The environment wins because fewer paper cups go to landfills. Filed under: Economic Theory, Environment, Market Efficiency Comments: 2 Comments

|

|

Posted at 10:16 pm on April 3, 2010, by Christine Harbin

In an op-ed published on Thursday, the editorial board at the Wall Street Journal criticizes Washington’s latest attempt to bail out homeowners. They argue that this intervention will be as ineffectual as the those that preceded it, and that homeowners would be better off if the government hadn’t intervened. From the editorial:

The practice of bailing out homeowners has several unintended negative consequences. The following are among the most egregious, in my opinion.

(1) Bailouts discourage employment. Just like any other type of unemployment benefit, payments to homeowners decrease an individual’s incentive to be employed. This contributes to a higher and longer-lasting unemployment rate.

(2) They penalize individuals who borrowed responsibly, and they encourage people to live outside of their means. Why put 20% down for a cramped ranch-style when you could buy a McMansion and have the taxpayers pay for it? (3) Many people bought houses that they couldn’t afford anyway, and they will foreclose on them in the future. For many people, a bailout is just delaying the inevitable. As described in a relatively recent article in the New York Times:

(4) They cause housing prices to be artificially high. Here is a Washington Post article on the subject. The latest proposal, like many of its predecessors, inflates home prices. Additionally, the $8000 homeowner tax credit allowed individuals to buy a more expensive house than they could otherwise afford. (5) There is a moral hazard problem. If a person knows that they are likely to be bailed out, then they are more likely to assume risk. I oppose bailing out people who bought houses that they couldn’t afford, and I disagree that the government should encourage homeownership. When a person invests her money, she assumes risk. Higher returns are supposed to be the payoff for accepting larger amounts of risk. Buying a house is just like any other investment outside of Treasury Bonds — there is a possibility that the individual will lose money. In some aspects, real estate is riskier than stocks because houses are not diversified (i.e., in the event of a natural disaster, a person’s entire investment is wiped out). A person should do thorough research before she makes what will be one of the largest financial decisions of her life. I recommend the article “5 myths about home sweet homeownership” by Joseph Gyourko, chairman of the real estate department at the University of Pennsylvania, in the Washington Post. It repudiates the commonly-held idea that homeownership is a investment that has good returns and no risks. To me, the following is the most eye-opening statistic in the article:

[Cross-posted at Amateur Philosophy.] Filed under: Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Uncategorized, Unintended Consequences Comments: Comments Off on “Homeowner” Bailouts and their Unintended Consequences

|

|

Posted at 11:12 pm on April 1, 2010, by John W. Payne

N.B. I wrote this post a few weeks ago for my personal blog before I changed the site to a new server, and it seems to have gotten lost in the shuffle. I happened to really like this one, so I went through the trouble of retrieving it and thought it was worth sharing here. I finished season two of The Wire last night (yes, I know I’m way behind on this one), and I thought there was a particularly interesting point about why governments fail running through the whole season. While the show is essentially an in-depth study of how different institutions fail, I think this one might warrant a little drawing out. (This post will not really have spoilers as such, but if you haven’t seen it, you likely won’t get it, so it might be time to stop reading now.) The whole reason for the detail’s existence in season two is because Major Valchek is angry that Frank Sobotka and his union gives a more substantial gift to the church they both attend than the police union. It is nothing more than a personal vendetta, which just happens to uncover a massive criminal conspiracy. Furthermore, if Valchek had his way, the worst of the conspiracy would have remained hidden just so he could pursue one of the least guilty members of it. Public choice economics holds that one of the major problems with government is that politicians and government employees do not cease to be self-interested once they become part of the government. They do not pursue some mythical “common good” but their own profit, and Valchek is the perfect illustration of that. To use one of his phrases, Valchek “couldn’t give a hairy-ass fuck” about some ideal like law or justice. For him, being a police officer is about rising within the organization as far as possible and abusing his power to get what he wants in the outside world. There are many “natural police” who do care about doing the right thing, but they are always crushed by the organization, while the Valcheks and Burrells rise to the top. And so it is with every governmental organization. Political decisions are almost never made with an eye to the costs and benefits of the whole society but merely the costs and benefits to the politician or bureaucrat. Contrast this with the gangs in the show. While there is a great deal of personal animosity between some groups (e.g. the Barksdale and Proposition Joe), it can almost always be set aside if it becomes necessary for the sake of business. At the end of the season the Greek says “Business. Always business,” and it’s a perfect statement for the mentality of almost all the gangsters on the show. They do some truly awful things to keep their business functioning–usually because of the black market nature of their businesses–but it is rarely for any personal reason. Their organizations exist for one reason: to sell a product that people want. If they lose sight of that, they will cease to exist. However, the police and other government organizations only theoretically exist to enforce laws and mete out justice. In reality they have as many different missions as there are personalities involved. What benefits one division of police, almost inevitably hurts another, so the organization can never be organized because no one can agree on its goals. The police can only muddle forward, fighting each other almost as much as they fight crime, while even if the gangs are feuding, the shit makes it to the street. Filed under: Drug Policy, Economic Theory, Market Efficiency Comments: Comments Off on The Wire and Public Choice

|

| Next Page » | previous posts » |

When I was a kid, I loved watching

When I was a kid, I loved watching

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."