|

Posted at 1:37 am on May 17, 2014, by Eric D. Dixon

Alexandria City Councillor Justin Wilson (no, unfortunately not that Justin Wilson) invited me to provide testimony for a food truck regulatory hearing, so here’s what I sent to him: Although I live just outside the city proper, in Fairfax County, Alexandria city is in many ways still my community. I shop at Giant, Whole Foods, and Trader Joe’s; I eat at Old Town restaurants and play trivia in Old Town bars; I watch plays at the Little Theater and watch movies at AMC Hoffman. Perhaps even more importantly, in two weeks my employer’s offices are moving from the Watergate to Duke Street, right at the edge of Old Town. I already spend a tremendous amount of time in Alexandria city, and I’ll soon be spending nearly all my days working here as well. There are a great many reasons to love Alexandria, but one thing this city is sorely lacking is a robust food truck culture. I have little doubt that existing brick-and-mortar restaurants aren’t excited at the prospect of competing with a horde of nimble upstarts who have lower overhead and fresh ideas. But competition breeds innovation, and food trucks both create and expand niche and otherwise underserved markets. An example close to my own heart can be found in my hometown: Portland, Ore. Only two years ago, a couple of paleo diet enthusiasts launched a modest Kickstarter for $5,000 to fund a food truck they planned to call Cultured Caveman. Now, regardless of what you think about paleo, there’s no question that this is a niche market. Dedicated paleo restaurants simply don’t exist — at least, they didn’t in 2012. But the Cultured Caveman folks found a groundswell of community support, easily surpassing their fundraising goal and expanding from one cart to three, spaced throughout town, in less than two years. Just this past March, they successfully exceeded a $30,000 Kickstarter campaign to open their first brick-and-mortar restaurant. There’s no way this couple of young, 20-something entrepreneurs could have gambled on a full restaurant right out of the gate, with no real capital, no experience as restaurant owners, and no idea whether they’d be able to attract a clientele with a menu so strictly limited in concept. But with a small level of overhead and a big dream, they parlayed a few thousand dollars into a citywide franchise that has made many thousands of Portlandians happy. People with celiac disease or lactose intolerance, people avoiding processed sugar and chemical additives, people who simply care about organic produce and grass-fed meat — they all now have a set of prepared-food options where they know that literally everything on the menu will meet their unique dietary restrictions. I don’t know whether Alexandria could be home to a success story of exactly this type, but my real point here is that nobody knows. We can’t know unless the political process steps out of the way of entrepreneurs who want to put their money at risk in order to bring the people of Alexandria new options. Let consumer preference reveal itself by lifting food truck restrictions and letting innovation flourish. Let us all find out which great untried ideas are out there that we’ll someday wonder how we ever lived without. [Cross-posted at The Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Uncategorized Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 12:42 am on January 24, 2012, by Eric D. Dixon

Public choice article of the day, from The Atlantic:

To be clear, although I’d like to avoid the consumption of antibiotic-treated livestock as much as possible, I don’t think the FDA should ban it — a clear overreach of government power.

If the FDA allows a product or practice, the public at large regards it as safe. If the FDA disallows something, society assumes danger. But instituting a top-down decision-making process to centralize the level of risk that consumers should be allowed to take leads to a system that serves nobody well. Life-saving drugs are barred from being used by people who are more than willing to accept their potential hazards. The sale of healthy food is criminalized because of the mere possibility that it could make somebody sick, despite the fact that people can and do get sick from the FDA-approved alternative. And, as shown in The Atlantic, because people trust that D.C. paternalists are looking out for them, they carelessly consume anything that the FDA has let slip through its otherwise iron grip. A bureaucratic overlord is incapable of choosing the correct balance between risk and reward even for the people in his neighborhood, let alone for more than 300 million strangers scattered throughout the country. There is, however, an alternative, as Larry Van Heerden noted in The Freemam:

[Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Corporatism, Drug Policy, Food Policy, Nanny State, Public Choice, Regulation Comments: 2 Comments

|

|

Posted at 12:10 am on December 10, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

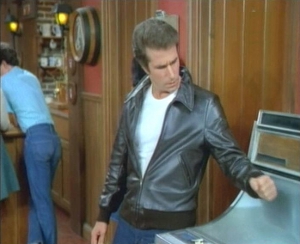

The Fonz could knock down doors with a slap of his hand, summon any girl with a snap, and most often on the show displayed his classic power of fixing the jukebox by banging on it. It’s a seductive fantasy that one might be able to fix a complex piece of machinery through an application of blunt force, without having to worry about the intricate mechanisms that actually allow the machine to work. Unfortunately, this is the mentality that has reigned for decades in applied public policy. Is the economy broken? Bang on it. That’ll get it chugging along again. Wait, that didn’t work? You didn’t bang it hard enough. Or maybe your leather jacket needs to be a little cooler next time. At any rate, it’s your fault. If you’d only smacked the economy the way that Fonzie showed you, it totally would have worked. Economic prescriptions thereby stem from a non-falsifiable tenet of faith in a grown-up power fantasy. This kind of magical thinking convinces many because it is accompanied by a veneer of rigorous thought. There are even equations! Surely, equations are scientific! But as economist Don Boudreaux pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

Keynesian macroeconomic variables lump heterogeneous goods and services into undifferentiated masses, no longer to be understood as the complex workings of a dynamic system of social cooperation. But just because you can gather a bunch of statistics and aggregate them into a variable doesn’t mean that the variable has a meaningful application to the real economy. If you want to fix a jukebox in real life, a mechanic might be able to get the job done by tinkering with the machinery until each piece once again functions correctly. It’s easy for people who have a facility with physical forms of engineering to take a similar view of the economy, thinking that if only the right people were in charge, they could tweak policy here and there to ensure successful outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith explained why the economy can’t be successfully engineered in such a way:

Even though an economy can’t be planned, or even tailored, successfully from on high, that form of scientism is at least understandable. It at least takes into account a small measure of the complexity of decentralized economic activity, even if it doesn’t — indeed, can’t — consider the rest. Keynesian macroeconomics is far worse, shunning even the scientistic attempt to grapple with at least some heterogeneous microeconomic factors as being the causal source of economywide trends. Instead, they insist that policymakers expropriate as much cash as humanly possible and wallop the economy with it as hard as they can. Economist Steven Horwitz summed up the real prescription for economic recovery:

In the end, the economy is not a jukebox, and neither a mechanic nor Ben Bernanke in the coolest leather jacket ever made can save it from its turmoils. Instead, the economy is made up of hundreds of millions of people with billions of plans, many of which fail but some of which succeed. Nobody knows for sure which plans will pan out in advance — not the people making them, and certainly not their public officials. Only by letting individuals, alone or in voluntary association with others, respond to local conditions with unique knowledge can the best plans be discovered, expanded, and replicated. That process is made much more difficult when they face continual interference from central planners who only pretend they can know what’s best. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 3:59 pm on October 26, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

Cafe Hayek‘s Russ Roberts tells the House Oversight Committee that he wants his country back. Highlights of his testimony:

And:

[Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Corporatism, Politics, Public Choice, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 12:05 am on October 19, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

Here’s a great cartoon from Completely Serious Comics published earlier this year, currently being passed around on Facebook by critics of Keynesian stimulus: I doubt the cartoon’s creators were thinking about government stimulus of aggregate demand when they conceived this, so it has become a piece of appropriated satire. And, like pretty much all great satire, it doesn’t play completely fair with its target. Even so, it contains a substantial nugget of truth. Readers of this blog who are familiar with the book from which it takes its name will be well-acquainted with the broken window fallacy, first created as a parable by Frédéric Bastiat and later appropriated by Henry Hazlitt, who applied it to a mid–20th century economy. In a nutshell, the parable explains why destruction doesn’t make a society wealthier. It may stimulate short-run economic activity as people rush to replace and rebuild what they’ve lost, but always at the expense of overall prosperity. Within the past few years, Bastiat’s and Hazlitt’s critical heirs have applied the fallacy again and again to modern Keynesians. Here’s a video that does exactly that to Paul Krugman’s application of Keynesian theory to the destruction wrought by terrorist attacks (featured on this blog last year): One objection to this line of thought could be that the broken window parable doesn’t apply to general stimulus, because government spending absent a disaster isn’t the same thing as destruction, and so isn’t analogous with a broken window. One response to this objection would be that the broken window parable is part of a larger essay about the unseen effects of various types of economic action. People explaining the arguments in the larger essay, which does indeed include government spending, might reasonably refer to them by invoking the best-known portion of that essay, the parable of the broken window. Conjuring the whole of an essay by referring to one part would be a kind of allegorical synecdoche, if you will. Another response would be that spending may not destroy useful physical objects, true enough, but it does divert resources from more productive to less productive uses. Although private-sector businesses can’t be sure what their most productive potential investment will be, the government is by nature even less informed and therefore less capable of investing wisely. Siphoning resources from the private sector to the public sector destroys wealth, even if it doesn’t destroy specific goods. An allegory of a destroyed object certainly applies to the reality of destroyed wealth. Keynesian apologists, and even some non-Keynesians, have cried foul in still more nuanced ways, pointing out that advocates of government stimulus don’t per se want destruction, and may not even think it will bring increased wealth, but think instead that it will increase short-term economic activity, increasing employment and smoothing over economically troubled times. There are indeed shades of meaning and intent here. Believing that destruction may benefit the economy in some structural way, thereby sustaining short-term damage for long-term gain, isn’t the same thing as thinking that any individual act of destruction will increase economic wealth. After all, as Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, entrepreneurs engage in short-term “creative” destruction all the time, writing off temporary losses as a necessary cost of pursuing their visions for long-term productive investment. The evidence, however, shows that government spending intended to stimulate the economy and smooth out the business cycle instead exacerbates the business cycle, leading both to higher peaks and lower valleys. As Russ Roberts pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

When there’s a downturn in the business cycle, there’s a structural problem with the economy — too many people in some occupations, not enough people in others. General stimulus provides no economic information about where people should go to find sustainable productive work, meeting real demands by providing the goods and services that people want rather than the trumped-up illusory demand prompted by government spending. You can’t build a healthy body on a string of sugar rushes, and you can’t build a healthy economy on a series of artificial top-down influxes of cash. Stimulus only spurs some sectors of the economy by dampening others, whether present or future. The more that government officials tamper with the economic signals that let entrepreneurs know when they should invest and when they should steer clear, the more skittish investors become. Regime uncertainty entrenches malinvestment, and keeps the economy limping along. So, Keynesians, please stop celebrating destruction as a cure for economic ills. If truly creative destruction needs to happen in order to move less productive resources into more productive uses, private-sector entrepreneurs have the decentralized knowledge necessary to determine which of their own resources need to be replaced or reshuffled. Government officials do not. The only real cure for our lagging economy is for the government to quit breaking windows. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 4:20 pm on March 5, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

H.L. Mencken summed up public choice theory in 1936:

[Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Politics, Public Choice Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 5:20 pm on January 15, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

This guy reinvents the lessons of “I, Pencil,” by trying to build a toaster from scratch: [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Gains From Trade, Technology Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 2:08 am on April 3, 2010, by Eric D. Dixon

Working as an intern for the Cato Institute in 1997 was one of the most formative experiences of my life. During that time, I participated with the other interns in a series of lunchtime discussions with Tom Palmer, a Cato senior fellow, director of Cato University, and also now with the Atlas Economic Research Foundation, where he’s vice president for international programs. I’ve written elsewhere about my high esteem for Tom, and his considerable impact on my own intellectual development, and I could say more — but for now, I’ll get to the point. The very first reading assignment that Tom gave to the interns was Frédéric Bastiat‘s essay “What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen.” It’s pretty powerful stuff, even today, and even for those of us for whom the ideas contained in that essay are old hat. That may be partly because of Bastiat’s clear, lucid, illustrative way of making abstract economic concepts understandable and unmistakable, but also because the economic fallacies that Bastiat debunked are still widely believed today, so his points remain relevant to modern political and social problems. When journalists — and even a Nobel laureate economist — begin to credit wanton destruction as a form of economic stimulus, it becomes obvious that Bastiat is more relevant than ever. Henry Hazlitt updated Bastiat’s essays for a new generation in his book for which this blog is named. Tom Palmer is helping to bring them to the YouTube generation. Tom has begun producing a series of video clips with Atlas that aim to take these fallacy-busting arguments viral. I’m far from the first person to link to this clip, and I’ll be far from the last. The belief that destruction — or, for the same reasons, government spending — can stimulate the economy in a useful way is a symptom of lack of forethought. Anybody reading this right now can help stem the tide of economic ignorance by passing on the link to friends, or suggesting it to the reading audience of whatever forum you might participate in. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Government Spending Comments: 5 Comments

|

|

Posted at 2:27 am on April 1, 2010, by Eric D. Dixon

The venerable Don Boudreaux linked to us from Cafe Hayek yesterday, calling us a “Great new blog” — a tremendous honor for our fledgling effort. Justin floated the idea for starting this blog only 10 days ago, I built the site later that night, and we started asking a bunch of our libertarian friends to join us over the next few days. I’m a little stunned we went in only nine days from tentative mental glimmer to getting name-checked by the chairman of the George Mason University Department of Economics, but the Internet is a pretty fantastic and fast-moving place. I had the good fortune to meet Boudreaux once, back in 2002, when he shared a Future of Freedom Foundation bill with Nathaniel Branden, the night before the Cato Institute’s 25th anniversary celebration. I sat next to Bumper Hornberger during the dinner, and he couldn’t have been nicer or more enthusiastic about spreading the ideas of liberty. At any rate, Boudreaux gave a speech pointing out the many ways that capitalism makes our lives better, safer, cleaner, and more pleasant — often in ways we take for granted because they’ve become so commonplace. It was essentially a lengthier version of this Cafe Hayek blog entry. It’s a theme that bears repeating often, such as in my blog entry from last night — or, as one of our commenters reminded me, in this Louis CK appearance on “Late Night With Conan O’Brien.” Back during the early ’00s when I lived and worked for about six years in the DC area (at U.S. Term Limits and Americans for Limited Government), I kept telling people that I planned to pursue an economics degree at George Mason. I even relocated from Maryland to Virginia in a blatant in-state tuition rent-seeking move. But then I got laid off from my job in the then-rapidly-contracting nonprofit world and my mom’s health took a turn for the worse — so I moved back out west, and eventually ended up in St. Louis where I live today. I often keenly regret not having taken the GMU plunge, though. If you’re a free-market econ geek, GMU’s program seems like one of the most exciting places on earth. To this day, I sometimes idly fantasize about applying, dropping everything, and moving to Fairfax. But grad school is really something I should’ve done a decade ago. I guess I don’t have a unifying point to all of this rambling, other than to say that Cafe Hayek is excellent, and anybody who happens to be reading our blog but doesn’t yet follow theirs regularly should rectify that today. Filed under: Blog, Economic Theory, Higher Education Comments: 3 Comments

|

|

Posted at 2:17 am on March 31, 2010, by Eric D. Dixon

David Boaz reminds us just how amazing markets are when they’re allowed to work:

This reminds me of the inspiring book by Stephen Moore and Julian Simon, It’s Getting Better All the Time: Greatest Trends of the Last 100 Years. The state smacks down the economy every day with its gigantic dead hand, and yet efficiency still finds a way through in many ways, continually improving our lives. Eliminating as much of that dead-weight regulatory loss as possible will absolutely make the world a better place. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Market Efficiency Comments: 5 Comments

|

| Next Page » | previous posts » |

The lesson here, though, is that when a government agency is tasked with protecting the public interest,

The lesson here, though, is that when a government agency is tasked with protecting the public interest,  When I was a kid, I loved watching

When I was a kid, I loved watching

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."